For the celebrities and criminals jam-packed into the East End church to witness the marriage of gangster Reggie Kray to his young bride Frances Shea, the tense atmosphere was not helped by the behaviour of his twin Ronnie as they awaited her arrival.

Cal McCrystal, one of the journalists invited to report on what the image-obsessed Reggie had promised would be the ‘East End wedding of the year’, noted how Ronnie added his own menacing twist to the role of best man as he sat in the front pew.

‘He kept shrugging his shoulders with impatience and turning around to glare at everyone,’ he recalled. ‘Very disconcerting’.

The tension on that Saturday in April 1965 became even more obvious when the organist launched into the traditional marriage hymn Love Divine All Loves Excelling. ‘No one was singing,’ said McCrystal. ‘It felt like very few of these people had even been inside a church before. Then, suddenly, Ronnie yelled out, “Sing, f*** you, sing!”

‘Unfortunately, that coincided with a break in the organ music. So they all heard it – and tried to obey Ron by making throaty noises.’

When Frances arrived, wearing a stunning confection of ivory satin and lace and clutching a posy of blood-red rosebuds, it was on the arm of her brother Frankie – her father, Frank senior, having refused to give her away.

He and her mother Elsie were among only a handful of people on the bride’s side, sitting glum and straight-faced with Elsie dressed in a pointedly funereal outfit. Yet another reason for Reggie to despise his mother-in-law.

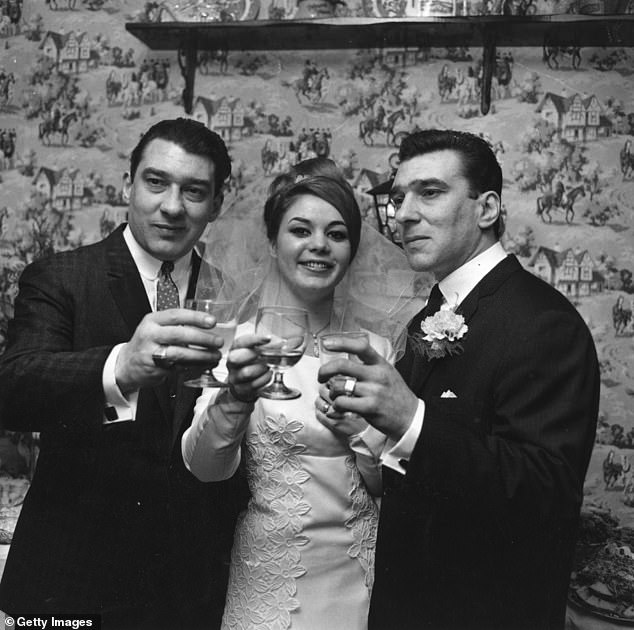

Notorious London gangster Ronnie Kray with brother Reggie and Frances on the day of their wedding in April 1965

The ceremony had to be conducted by a junior priest called Father Foster because his senior colleague Father Hetherington, who had known the twins for years, had refused to officiate.

How well he understood that this marriage, born out of Reggie’s desire to present himself to the world as a normal, respectable man with a beautiful young wife, was never going to be anything other than a fake in every way.

There was no joy or sense of celebration during or after the service. It was a media event, no more, no less, with David Bailey, an East End boy whose fame was already soaring sky high in the Sixties, arriving at the church in a blue Rolls-Royce and taking photos as a gift to the couple.

The reception was at a hotel in north London where only three months previously the twins had been arrested on charges of demanding money with menaces, also known as blackmail – a rap they escaped by hiring the best and most expensive lawyers.

Afterwards, the bride’s brother Frankie went home with a heavy heart, convinced that Reggie had only started dating his sister as an act of twisted sexual revenge.

Both of the Kray twins had been having sex with men since their teens and Ronnie wasn’t exactly shy about his preferences – for ever surrounded by a coterie of handsome youths, preferably heterosexual so that he could claim to have ‘turned’ them.

Reggie never openly showed any signs of being interested in men but his second wife Roberta confirmed in her book Reg Kray: A Man Apart, that he had ‘experimented, as many young men do,’ finally acknowledging in his 50s that he was bisexual.

One horrifying example of this experimentation was described by south London protection racketeer Billy Howard. He claimed that one night the twins drove to the so-called ‘meat rack’ of male prostitutes outside the Regent Palace Hotel, near Piccadilly Circus, and picked up a youth.

Frankie Shea at his sister Frances’s wedding. A young car dealer, Frankie struck up a friendship with Reggie until one night he awoke in his car to find Reggie attempting a sex act on him

According to Howard, they broke into a house in Chelsea and made use of the rent boy simultaneously, choking him to death in the process. They then put the body in the boot of the car and disposed of it in Norfolk, one of the many crimes that the Kray twins would never be held to account for.

While their mother Violet was tolerant of homosexuality, their father Charlie senior couldn’t disguise his dislike of what they were doing and it was he who intervened on the night that Reggie made a move on Frankie.

Frankie and Frances were raised by Frank and Elsie, a woodworker and a seamstress, in a tiny terrace house in Shoreditch, about a mile from the Kray family home in Vallance Road, Bethnal Green.

Two years older than Frances, who was born in September 1943, Frankie had dark good looks and, by the age of 18, he was establishing himself as a car dealer – soon attracting the attention of Reggie Kray, who was looking to replace his own vehicle at the time.

They struck up a friendship that led to Frankie becoming Reggie’s chauffeur. ‘He was a good-looking kid with brown eyes, dark hair and an olive complexion,’ recalled Reggie in his autobiography.

‘As a driver he was the best I had come across, while his personality made him exceptional company.’

One night, when they’d all been drinking too much, Frankie went back to Vallance Road with Reggie. After passing out, he woke up with a start to find Reggie attempting oral sex on him.

Panicked, he started shouting and screaming, loudly enough for Charlie senior and one of Reggie’s uncles to hear him and, thankfully, step in and pull the inebriated Reggie away in disgust.

Ashamed and scared, the teenage Frankie had quickly dived for his stuff and bolted out into the street. The discovery that someone he’d looked up to wanted to do those things to him shocked and frightened him.

This was a man with a reputation for a killer punch. His twin was renowned for his preference for cutlasses and knives over razors – more power in the slashing. What was going to happen now?

The answer appeared to be nothing. The next time he saw Reggie in the shabby, run-down billiard hall which had become the Krays’ operation base, he acted as if the whole thing had been a dream.

Frankie was relieved. Reggie seemed to have got the message. But then, without warning, he was taking Frances out. In Frankie’s mind, there was never any doubt: Reggie had started courting Frances to get back at him for that drunken rejection.

Ten years her senior, Reggie would later claim that he met Frances while visiting Frankie at the Shea house when she was 16.

But this is contradicted by his own letters to her, revealing that she was only 15 and still at school at the time. People later presumed that she was a classic gangster’s moll, a good-looking clothes horse who was not especially intelligent.

In fact, she was a grammar school girl who, suffering from depression even before her relationship with Reggie, sought solace in poetry and literature.

In one of her notebooks she copied out Maud, a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson which makes for chilling and prophetic reading, dealing as it does with themes of suicide and other untimely deaths.

In other ways, she was a typical teenager of the time. She liked dancing, reading women’s magazines, checking out the latest fashions, getting her hair done.

Reggie would be chuffed when one of his friends told him that Frances looked ‘just like Brigitte Bardot’. To him, she represented a trophy, someone to show off as a partner for the successful businessman he believed he’d become.

He later told the pretty, auburn-haired girl with the big eyes that he had fallen in love with her at first sight.

He certainly seemed convinced that he had, but love and obsession are very different things and Reggie was as determined to own her, body and soul, as Ronnie was to drive them apart.

Ronnie had always stamped on any hint of Reggie’s attraction to the opposite sex as a threat to their twinship. Women, he would tell Reggie, ‘smell and give you diseases’. He thought his brother was being a cissy looking at them.

‘Ain’t she got ’orrible legs,’ he’d say about Frances. The sneering and jibing led to furious fighting between the brothers.

While Reggie saw creating an aura of menace around the twins as a way of making real money from their gambling clubs, pubs and businesses, Ronnie was violent just for the fun of it.

In November 1956, he had been jailed for three years for his part in murdering a rival gang member in a psychotic attack in a local pub, and this had been a turning point for the twins.

For the first time since they were three, when a bout of diphtheria separated them in hospital, they were apart and Reggie started to focus more clearly on what he wanted. Without Ronnie goading him and dominating his existence, he had started to see the appeal of a more ‘normal’ existence, involving a nice home with marriage and children to complete the picture.

This was another reason for him to pursue Frances, an impressionable teenager lured by the glamour of a good-looking, older man with expensive tastes in both cars and clothes.

Although he was a lousy driver, Reggie was mad about new cars and would draw up outside the Sheas’ humble East End two-up, two-down in a dazzling green Mercedes-Benz saloon, an astonishing sight around those still-battered post-war streets.

For Frances, being with Reggie represented a golden pass for entry into the dazzling world of the movie star, the nightclub maître d’ and the starched white tablecloth. After she left school at 15 to take a clerical job on the Strand he would meet her after work and they’d go to the movies.

There were drives out to the country. He’d buy her clothes, jewellery, give her cash.

The six years of their courtship followed a disturbing pattern: Reggie dropping Frances off at her parents’ house after a night out then continuing his usual nocturnal life with Ronnie in their ugly, blood-drenched and repressive world.

In the summer of 1960, Reggie was jailed for two years for his involvement in a protection racket. In prison, he had far too much time on his hands to dwell on his obsession with his teenage girlfriend. Paranoid in the extreme, he couldn’t stop thinking about her or about how, in his absence, someone else might decide they wanted to take Frances out. Or turn her against him.

On September 2, 1960, he wrote to Frances, telling her he was in such a bad mood at not receiving any letters from her that ‘I nearly choked a fella in my cell for having too much to say’.

After his release, they spent weekends together at the family’s caravan in Steeple Bay, Essex, just the two of them. There, Frances felt they were like any other couple, but most of the time Reggie inhabited the gangster world. In the years to come, this resulted in frequent rows between Reggie and Frances and sometimes she’d tell him it was all over. But he’d insist they had a wonderful future together and she’d relent.

But there was a nagging question at the back of her mind: suppose she did break off with Reg for good? Who was going to dare to take out ‘the Kray bird’? If she wanted a new boyfriend, she’d have to find a very brave man indeed.

Trapped in the Kray web, her means of switching off from the increasing terror she felt was to start taking ‘purple hearts’ – a combination of amphetamine and barbiturates hugely popular in the early Sixties.

Reggie took the same drugs himself but his cousin Rita Smith recalled him going mad when he heard about Frances taking them.

‘He found out who was supplying them and he never supplied her again. Or anyone else.’ This was yet another indication of the control Reggie wanted to exert over every aspect of life for his ‘living doll’, as he called Frances, after the Cliff Richard hit of 1959.

The Krays were intense and possessive by nature and much of Frances’s anxiety came from the increasingly scary Ronnie, whose violent impulses continued to scare the life out of everyone in their gang – known as the Firm – and to horrify his twin.

One night at the Cambridge Rooms, a Kray-controlled restaurant on the outskirts of London, Ronnie went on a vicious knife-slashing spree, slicing open the face of an associate he believed had insulted him.

Doctors had to put in 70 stitches to repair the man’s face and only Reggie’s speedy persuasion of potential witnesses that they’d be better off staying silent saved him.

Later in that autumn of 1963, there was another horrific incident at Esmeralda’s Barn when a demented Ronnie branded a man along each cheek with a red-hot poker. Reggie worried that Ronnie was becoming so dangerous he might wreck their livelihood and believed he could ‘escape’ by marrying Frances. For her part, she was getting close to being left ‘on the shelf’ by the East End standards of the day.

Girlfriends were already married, expecting their first child, and she knew that Reggie wanted children. ‘Reggie loved children,’ recalled his cousin Rita. ‘He used to say to me, “Don’t babies smell nice?” He would have loved kids.’

His generosity to Frances knew no bounds and when she agreed to marry him he got her a fashionable red Triumph Herald.

The announcement of their marriage came in April 1965 when the twins were released from remand in Brixton Prison, where they’d been awaiting trial on those blackmail charges. As his twin climbed out of the fawn Jag that had transported them home from prison to Vallance Road, Reggie hugged Frances and told the waiting Press how happy he was to be back with his sweetheart. Yes, they were getting married. Yes, it would be very soon.

Frances cuddled their little dog, Mitzi, and posed for photos with Reggie. Her hair was now a reddish blonde and her Indian cotton smock-top a fashion statement.

For that brief moment in the spring sunshine, it seemed Frances had convinced herself that Reg’s dreams of their golden future were becoming reality.

Reggie Kray appeared to be her knight in shining armour. But was he? Or had Reggie merely told her she had no choice – that if she didn’t marry him, there would be trouble ahead for her family.

Frances’s father had also been woven into the Krays’ web, working as a croupier at one of their clubs. But her mother Elsie wasn’t fooled by any of the twins’ two-faced posing with film stars such as Judy Garland. She knew they went round knifing people, doing terrible things to anyone who stood up to them or got in their way.

Eventually Frank Snr sided with his wife and declared that the wedding could not happen. But Frances ignored them and focused on her big day, choosing the dress, working out how she’d do her hair.

Helpless against the might of the Kray twins, there was nothing her parents could do to stop what Reggie promised would be the East End wedding of the year but, as we will see in tomorrow’s Mail on Sunday, they had every reason to fear for both their daughter’s future and their own.

Adapted from Frances Kray – The Tragic Bride by Jacky Hyams (John Blake, £9.99). © Jacky Hyams 2014. To order a copy for £8.99 (offer valid to 26/04/25; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937