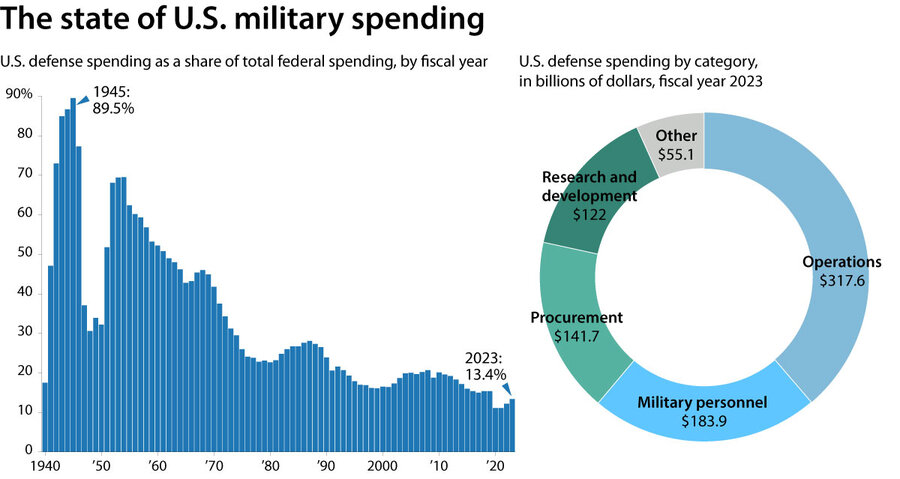

President Donald Trump last week promised that the new Defense Department budget will be the first ever to reach $1 trillion.

“Nobody has seen anything like it,” he said.

A defense budget of this size would mean that the U.S. armed forces will get a 12% increase from roughly $892 billion this year. But with spending priorities like a “Golden Dome for America” missile defense system that could cost $50 billion in next year’s budget alone, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth has also ordered the services to come up with 8% reductions to their budgets over each of the next five years.

Why We Wrote This

Even supporters of defense spending say the budget can be cut. One challenge is not to wipe out items that could affect recruitment or military families’ morale.

President Trump has also signaled his intention to make some Pentagon reductions. Last week, in addition to calling for the record budget, he issued an executive order for the Pentagon to review all major weapons programs and consider “for potential cancellation” any that are more than 15% behind schedule or over budget.

The money the services save would go toward the administration’s top military priorities, which include, defense officials say, operations at the southern border and deterring a militarily capable China.

The Trump administration has cited 17 budget items that are exempt from cuts, including submarines, attack drones, and the modernization of America’s nuclear arsenal.

Even defense hawks have long lobbied for many expected reductions – for example, to weapons systems that in their slow development have been overtaken by new technology.

Other potential cuts, such as the downsizing of Army forces and services that support troops and their families, are being eyed because they are too pricey or don’t contribute to the administration’s goal of “lethality.” But analysts warn that trimming them could jeopardize precarious recruiting efforts.

Now as Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) turns its eye on the Department of Defense – having already dismissed hundreds of probationary civilian employees before hiring some back – it’s time for the services to take a hard look at their spending, says retired Brig. Gen. John Ferrari, who previously served as the top evaluator of Army programs at the Pentagon.

Otherwise, Mr. Musk’s workers – less versed in military strategy, but with technical tools that the Pentagon should have long ago applied to its budget process – will find them first. “It’s DOGE or be DOGE’d,” Mr. Ferrari says.

Updating technology could help military cut spending

As Mr. Ferrari was searching for ways to cut the Army’s budget during the first Trump administration, he decided to convene a “night court.”

Much like its namesake sitcom, he says, “It was speed – and it was summary judgement.”

Officials in charge of some 500 major defense programs came before two judges – the secretary of the Army and the Army’s top officer, the chief of staff – to defend their budgets.

“My job was to keep the docket moving,” Mr. Ferrari said. “It was, ‘OK, that’s enough. Kill it? Keep it? Next, next, next.’”

Appeals had to be made in person on the last day. The line ran the length of a Pentagon hallway.

The first person left with another 25% cut to his budget, and the queue quickly dispersed.

The DOGE-like process trimmed $25 billion, says Mr. Ferrari, now a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Today, new software can help services better identify waste. But the Pentagon has been unable to pass an audit since it was required by law in 2018 in large part because it’s been using “vastly outdated electronic platforms and record keeping,” says Katherine Kuzminski, director of studies at the Center for a New American Security. “And I think this is exactly the kind of space where the tech-focused group of individuals in DOGE could do a lot of good.”

Because of this outdated technology, answering questions that could help with cost savings – such as “How many people in uniform today are on sick leave?” – is “much more difficult than it should be,” she adds.

The Marine Corps is a model for putting in place systems that can track “the moving pieces” that point to budget inefficiencies, whether it’s “up-to-date inventory of weapons supplies or spare parts for airplanes that are no longer in use,” she adds.

At his first town hall, Secretary Hegseth congratulated the Marine Corps for being the only service yet to pass an audit. “Y’all got it figured out, and we appreciate that – lean and mean,” he said.

Secretary Hegseth late last month also canceled more than $580 million in programs, the largest being a civilian human resources software system that was supposed to take a year to develop at a cost of $36 million and is now some eight years behind schedule and $280 million over budget.

“DOD is simply awful at procuring software,” Mr. Ferrari says, in part because it “tries to customize every line” and in so doing makes it into a “hand-built, exquisite, never-to-be-replicated mess of code.”

Defense analysts predict where cuts will fall

In listing its defense priorities, and through well-publicized social media comments, the Trump administration has made no secret of the sorts of spending it does – and does not – want to see.

Elon Musk, who has no military experience, has called tanks “a death trap,” for example, and has criticized F-35 fighter jets for trying to be “too many things to too many people.”

The Pentagon will also use budget funds to end “radical and wasteful” diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, Robert Salesses, acting deputy defense secretary, said in a statement last month. Defense officials have directed military forces to scrub websites of diversity, equity, and inclusion references and to remove from military academy libraries literature and history books that the administration deems harmful to unity.

To explore budget items that haven’t been as well publicized, a group of roughly a dozen analysts from top Washington think tanks that spanned the political spectrum took part in its own exercise last month. The goal was to predict the sort of budget cuts and purchases most likely to be necessary in carrying out the administration’s plans.

Most agreed that the Navy and the Space Force would be the overall fiscal winners. Navy assets will be key to fighting China in any conflict, and the Space Force has a special role to play in a “Golden Dome” missile defense system.

“I think we can probably bank on that [demand for the Space Force] is only going to grow,” said Melissa Dalton, senior adviser for defense budget analysis at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and, until last May, a principal adviser to the secretary of defense.

On the other hand, the Army should brace itself for losing resources, including in combat brigades and special operations forces – two items that participants across the political spectrum predicted would receive cuts in the recent exercise.

“Like most people coming from a restraint camp, we would like to have no U.S. forces in the Middle East,” said Jennifer Kavanagh, director of military analysis at Defense Priorities think tank. In Europe, the administration has been arguing for the United States to play “a much smaller role” in the continent’s defense, she added.

In the Army, while former Chief of Staff Randy George proposed cutting 5% of generals, DOGE “will be looking for something like a 50% reduction,” Mr. Ferrari says.

Cutting force structure allows the Army to buy less equipment and fewer vehicles as well, analysts say.

U.S. forces are expensive because they come with personnel costs like health care and pension plans, too.

During the think tank exercise, participants predicted cuts to military schools for dependents and grocery stores on bases, because they did not advance, in Mr. Hegseth’s words, “military capability and lethality.”

Yet analysts caution that given the recruiting challenges the U.S. military is facing, “Anything we do that compromises our ability to offer a good life to military families runs the risk of exacerbating that,” Michael O’Hanlon, senior fellow in foreign policy at the Brookings Institute, said in a press briefing following the exercise.

At the same time, he added, despite discussions of burden sharing, there are capabilities from pandemic control to responding to natural and human-made disasters that “Nobody else in the world can do.”

Even many of those in the restraint camp argue that unexpected future events necessitate more forces than cuts may currently anticipate. As with the 9/11 terrorist attacks that led to conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan that lasted for nearly two decades, the next U.S. wars – along with the weapons and special training that the U.S. military will need to fight them – are difficult to predict.

“I really do think that [former Defense Secretary and CIA Director] Bob Gates was right when he said we’ve got a pretty perfect track record of predicting the future of warfare,” Dr. O’Hanlon said: “We always get it wrong.”