The Women’s Orchestra Of Auschwitz by Anne Sebba (Weidenfeld & Nicolson £22, 400pp)

The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz is available now from the Mail Bookshop

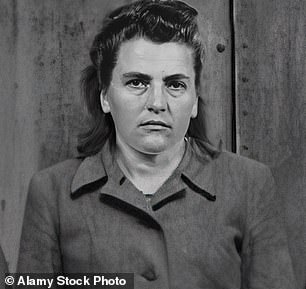

Maria Mandl, known as ‘The Beast,’ was the sadistic SS chief guard at Auschwitz-Birkenau who founded the women’s orchestra.

Notorious for her brutality, Mandl smiled while selecting prisoners for the gas chambers and was known to kick a woman to death.

She imposed roll calls from dawn to dusk in sub-zero conditions, leaving women frozen to the point of immobility before pulling them aside to be gassed.

She took children from incoming transports, held them, sang to them, and then escorted them to their deaths.

The more vicious, the higher in the ranks she rose.

It feels impossible to reconcile the exceptional brutality for which Mandl was known with her professed love for music but she was part of a system in which cruelty and culture coexisted, where murderers could appreciate Mozart and still commit atrocities without a flicker of conscience.

Anne Sebba is unflinching about the camp atrocities, describing shocking instances of cannibalism where starving prisoners ate the stolen organs of their dead campmates in their desperate bid for survival.

On Mandl’s watch, young violin student Eva Benedek, initially safe within the orchestra’s protective ranks, proved unable to escape death once her burgeoning pregnancy was discovered.

Permitted to deliver her baby, she was then deprived of food and so unable to nurse him. The baby starved to death in her presence, after which she was gassed.

In this deeply affecting book, Sebba reconstructs the experiences of the women, both Jewish and non-Jewish, who played in the orchestra in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

There is a terrible paradox at the heart of the orchestra’s very existence, an unbearable intrusion of beauty into the ugliest place imaginable. While for some prisoners it may have offered momentary comfort and an illusion of freedom, for others it was a cruel reminder of the lives they had lost.

The orchestra performed daily, playing marches while starving prisoners were forced to and from work in the nearby factories; entertaining the whims of SS officers after their rounds of mass murder; and creating a grotesque illusion of normality for newcomers to the camp.

Instruments were stolen from Jewish prisoners who had arrived carrying their most treasured possessions, unaware they were about to be stripped of everything, including their lives.

Survival in Auschwitz was arbitrary, dependent on the whims of guards, the possession of a skill deemed useful, or sheer luck.

Initially, Jews were excluded from the orchestra, but demand for women musicians led to their inclusion and it soon became a microcosm of the wider world, marked by tensions between Jewish and non-Jewish musicians.

Their varying talents and consequent entry into the orchestra was, in pianist and accordionist Flora Jacob’s words, a ‘doorway to life’. Jews have long been encouraged to acquire portable wealth: knowledge and skills that cannot be taken away, as they have so often faced displacement, persecution and confiscation of property.

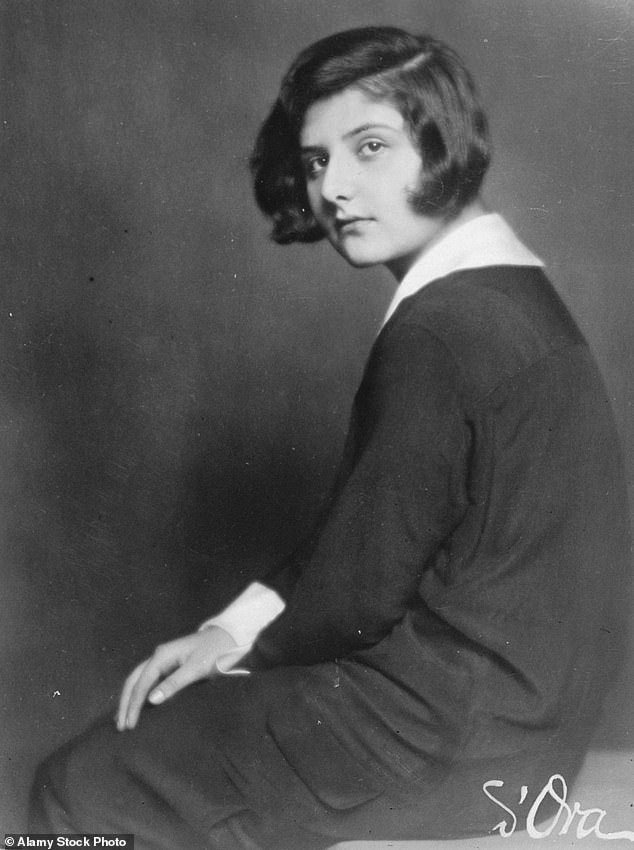

Sebba’s book is full of remarkable individuals, such as Alma Rose, the Austrian-Jewish violinist and niece of Gustav Mahler. After the orchestra’s first conductor, Polish non-Jew Zofia Czajkowska, was ousted by Rose’s superior talent, Rose became both protector and a taskmaster.

Once made conductor Alma Rose began replacing non-Jewish musicians with Jewish players, saving 40 extra lives as a result

She was ruthlessly disciplined, pushing the women to maintain a standard of excellence because she knew their survival depended on it.

Rose strategically decided to replace non-Jewish musicians with Jewish ones whenever possible, knowing that the non-Jewish players, many of them political prisoners, were not in danger of the gas chambers. It was a decision that saved 40 lives; however, her position was fraught with moral dilemmas.

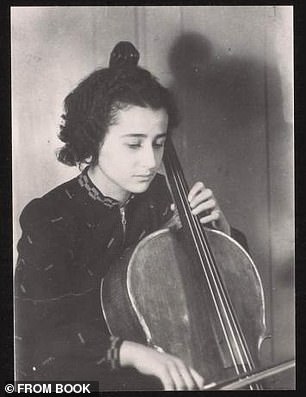

Many of the women questioned whether their survival had come at too high a price. However, as Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, the orchestra’s cellist, now aged 99 and the last surviving member, bluntly put it: they had no choice.

And yet, there is something deeply disturbing in the knowledge that SS officers, among them Josef Mengele, would demand particular pieces of music then return to their gruesome selection of who should live and die. Mengele’s choice was Schumann’s Traumerei (Dreaming), a piece from his Scenes Of Childhood.

What stands out most in this book, beyond the horror, is the ultimate resilience and solidarity among these women. In a place designed to strip them of their humanity, they clung to one another. They shared food, protected the weakest among them, and found small ways to defy their captors.

Despite the danger, Alma Rose dared secretly to play forbidden compositions by Mendelssohn, whose Jewish heritage made his music unacceptable under Nazi ideology.

No choice: Many of the women, including Anita Lasker-Wallfisch (pictured), felt morally compromised by their involvement in the Orchestra and the slight priviledge it afforded them

As the war neared its end, the Jewish members of the orchestra were transported to Bergen-Belsen. They had no idea whether this move meant a chance at survival or merely another stage in their extermination. Sebba’s description of the camp’s liberation is deeply moving.

However, liberation was not the end of suffering. The women carried the scars of Auschwitz for the rest of their lives. Some never touched a musical instrument again, unable to separate their art from the horror it had been forced to serve. Others constantly questioned if they had done enough to resist.

What makes The Women’s Orchestra Of Auschwitz so powerful is its unswerving commitment to detail. Sebba ensures that every woman’s name, every story, is documented.

This is not a faceless tragedy, it is a collection of individual lives, each deserving of remembrance. In Jewish tradition, when someone dies, we say, May their memory be for a blessing. This book is a deeply felt articulation of that sentiment.

There is added poignancy in the wake of the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz as the last survivors leave us, passing on the responsibility to bear witness to the next generations. This book reminds us that extremism does not emerge in a vacuum and that dehumanisation can happen in increments.