This article is taken from the March 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

The Venn diagram that connects the world of light literature to the New Year Honours List is an increasingly tiny space, but the Secret Author was able to raise a glass last month at the news that Caroline Michel had been elevated to a Damehood.

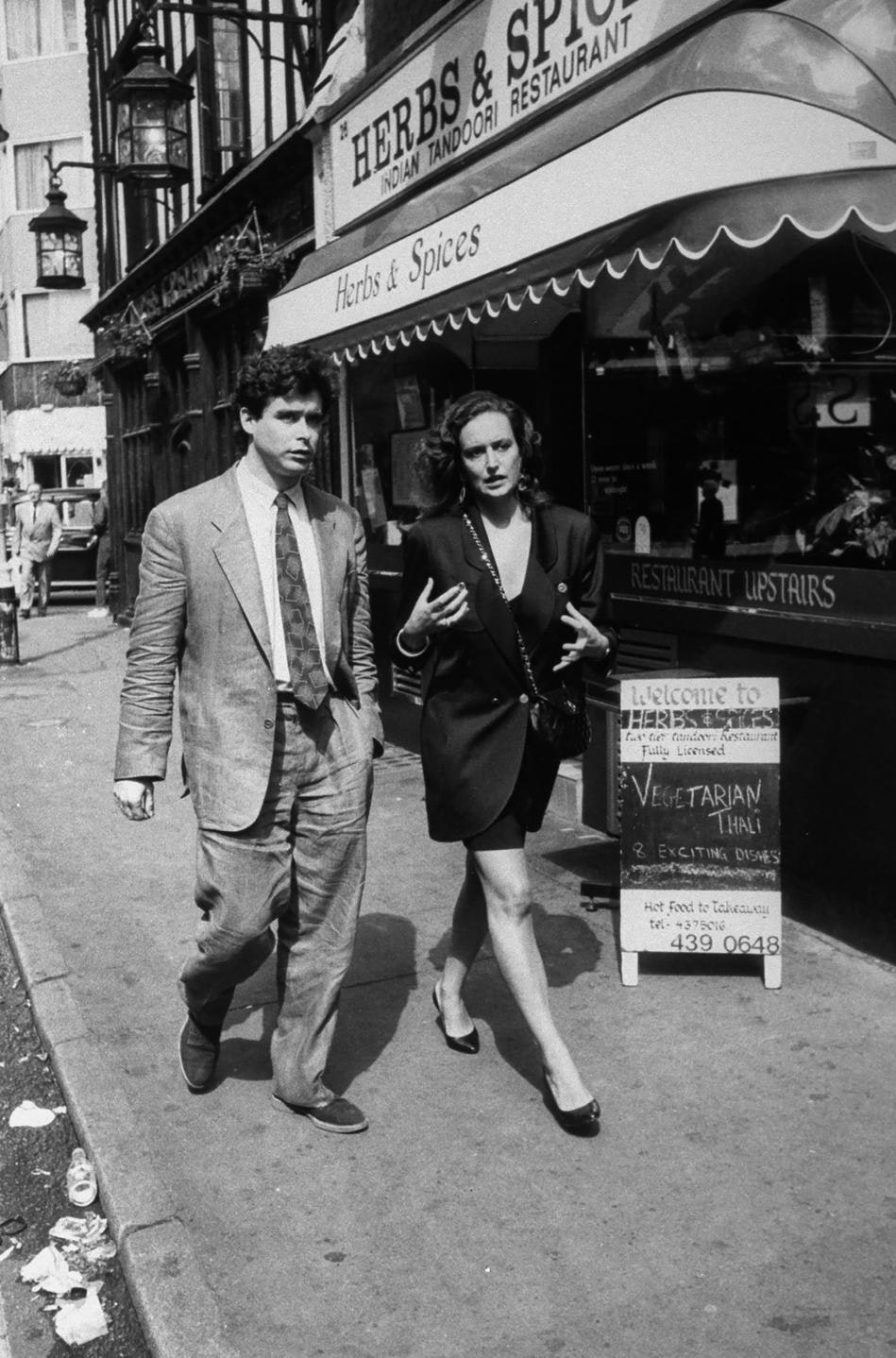

These days Ms Michel — Dame Caroline — is a high-powered literary agent-cum-eminence grise, chair of the Hay Festival and God knows what else besides, but back in the late 1980s she was the publicity director of Bloomsbury. It was in this capacity that the Secret Author first met her, hobnobbed with her in elegant West End wine bars and, more important, had the honour of being promoted by her.

The spell that she cast over Grub Street in that far-off decade was altogether paralysing. Literary editors flung themselves at her expensively-shod feet. Radio producers clamoured to be allowed to feature her authors on their programmes.

Coming back once to the Bloomsbury offices in Soho Square after a brief sandwich lunch, here in the pre-internet era when messages had to be fielded by the receptionist, the Secret Author stood by astonished as she was presented with no fewer than 53 Post-it notes.

On another occasion, receiving an invitation to a book launch at an address in Belgravia, he jocularly remarked, “Don’t tell me, Caroline, that one of your directors can afford to live in Eaton Square.” “Actually, darling,” Ms Michel assured him, “I do.”

If no other book-world publicity queen quite matched Dame Caroline’s stratospheric levels of resourcefulness and attack, then there are several who ran her pretty close: Gail Lynch of Chatto & Windus, for example; or the legendary Joanna Mackle of Faber & Faber, known for her extravagant hats and for calling out Chuck Berry for some bad behaviour in a taxi in front of a room full of applauding journalists.

What distinguished them, by and large, was the certainty of their predictions. If they said they were going to get you on television, darling, then they got you on television. If they said you were going to get the lead review in the Sunday Times, courtesy of Professor Carey, then Professor Carey shaped up. It was as simple as that.

There are several explanations for the triumphant march of Mesdames Michel, Lynch, Mackle and others over the publishing landscapes of the 1980s and 1990s. One, naturally, is the sheer force of their personalities, but another has to do with the immense trendiness and marketability of books at that time.

Print journalism was flourishing — there was a brief period when Fleet Street ran to no fewer than five quality Sunday newspapers — arts coverage expanded, serialisation deals could be used to underwrite big advances, and a publicity director with a hot property to promote could often spend more of her time turning potential interviewers down rather than signing them up.

All that, alas, was 30 years ago. Who would be a publicity director here in the age of digital media and, let us be frank, a world where books are not the draw they once were? To begin with, print space is declining — The Times and the Sunday Times still run to a decent eight pages, but I can only manage a two-page spread, and most of the serious coverage has migrated elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the BBC’s commitment to books grows more laughable by the month. What with regional radio cut-backs, even the out-of-town stations are less hospitable to that once-reliable airtime-filler, “the local author”.

Back in the 2000s, a reasonably well-known writer with a new book out could expect coverage in most of the main newspapers and magazines and perhaps an appearance on Open Book. Nowadays, he or she will probably be gratified by a blog spot from somewhere in Ireland or an invitation to supply a “What I’m Reading This Week” column (unpaid) to the Cleethorpes Advertiser.

Another difficulty is the increasing lack of interest shown by print media in what the big publishing houses put out. Literary editors are sensitive souls. They prefer to print reviews of good books by people who can hold a pen. In the absence of such volumes from the imprints with whom they customarily deal, they are likely to turn to smaller firms.

Not long back, to particularise, the Secret Author was interested to read the reviews of a novel entitled Season by a writer named George Harrison. Despite the obscurity both of Mr Harrison — this is his first work — and his publisher, Lightning Books, it was reviewed in both the Daily Telegraph and the Irish Times — venues that most debut novelists would give a limb to colonise.

Why was this? You suspect it was because Mr Harrison’s novel, though modestly brought out, possessed virtues that the month’s offerings by messrs Cape, Faber and Fourth Estate did not. All of which makes the job of the modern publicity director well-nigh impossible to sustain. No wonder Caroline Michel went off to become a literary agent and a DBE.