Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature

by Alison Hokanson & Joanna Sheers Seidenstein, with Essays by Joseph Leo Koerner & Cordula Grewe

(New York: The Metropolitan Museum Of Art, distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2025)

ISBN: 978-1-58839-789-8 (hardback)

296 pp., many col. & b&w illus.

£40.00

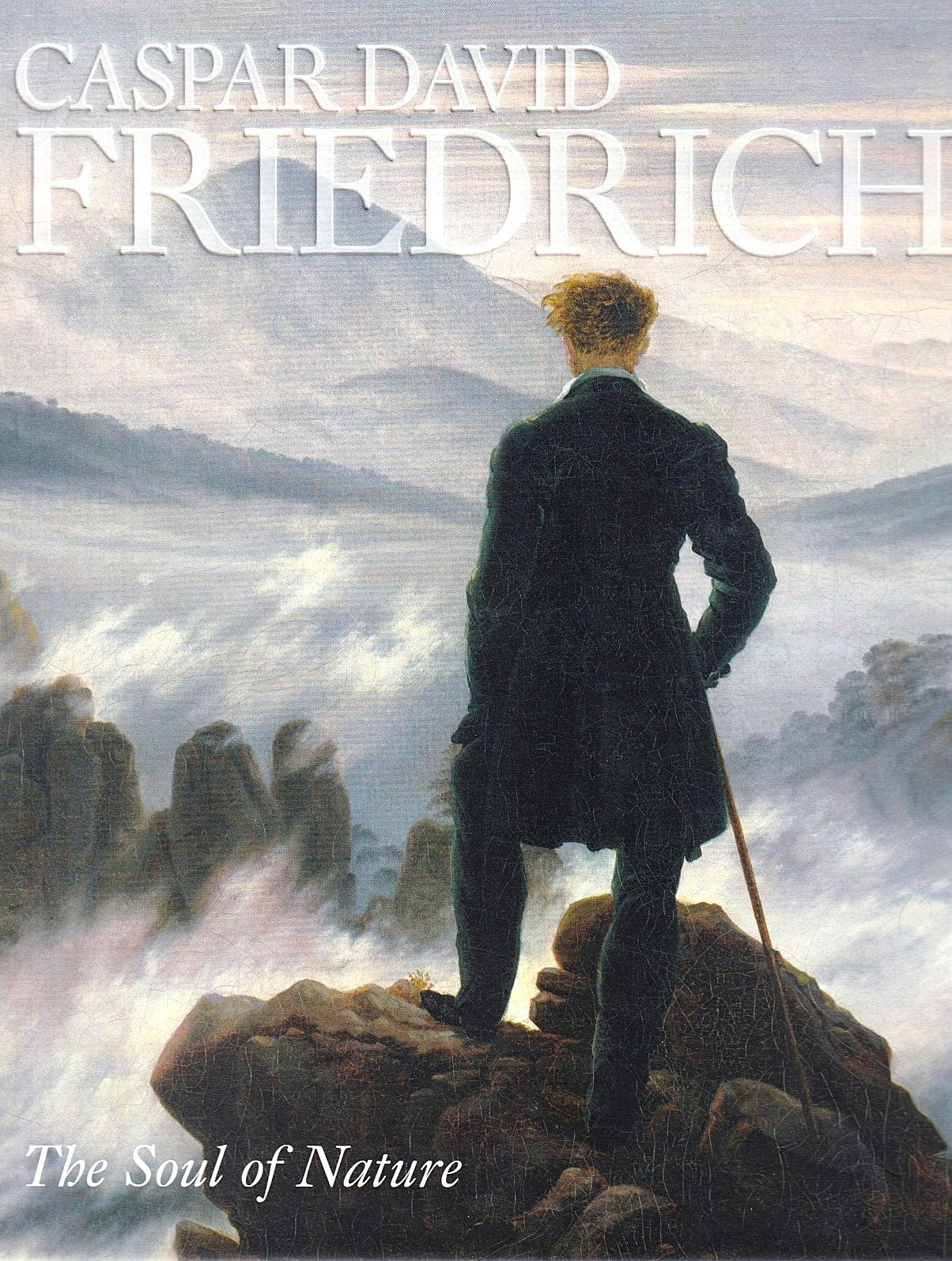

This tome, produced to accompany a major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (8 February to 11 May 2025), and published in association with Yale University Press, celebrates and analyses the astonishing, beautiful, and haunting work of the great German Romantic artist, Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840). It features on its cover his famous painting (c.1817) entitled Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, with its mysterious Rückenfigur (a person seen from behind) standing on what seems to be the rock formation Friedrich drew in 1813 when climbing the Kaiserkrone, a peak in the Elbsandsteingebirge (the Elbe sandstone mountains). Other elements of the landscape derive from the Zirkelstein massif and the Rosenberg, a peak in the Bohemian Elbsandsteingebirge, and the rocks of the Gamrig, just east of the Saxon town of Rathen, nor far from Dresden, where Friedrich had settled (he was born in Greifswald in Pomerania) in 1798. So the landscape depicted is an amalgam of several.

Although I had seen images of some of Friedrich’s works when I was very young (my grandfather had visited Dresden in the 1920s, and had bought the illustrated catalogues of the collections there), the exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London (6 September to 15 October 1972) was revelatory, and the fine and splendidly illustrated Catalogue by the distinguished German art historian, Helmut Börsch-Supan (b.1933), with contributions from Sir Norman Reid (1915-2007), William Vaughan (b.1943), and Hans Joachim Neidhardt (1925-2024), published to accompany that exhibition, still graces my library (it then cost the princely sum of £2.50). My own travels later in Saxony and elsewhere in Mitteleuropa led to my further appreciation of Friedrich’s methods: he was obviously strongly aware of the intricacies and wonders of Nature, and his meticulously fine drawings of details make this very clear, but in his paintings he disregarded topography, combining elements of what he had studied in newly imagined compositions. A prime example of this is his removal of the ruined Pomeranian abbey of Eldena near Greifswald to the Riesengebirge, the mountainous part of the Sudetenland lying on the border between what is now Poland and the Czech Republic, the equivalent, as William Vaughan explained in his essay on Friedrich in 1972 to depicting what remains of the great abbey of Fountains in Yorkshire in a new setting far away in the Scottish Highlands. Even “works with the greatest appearance of actuality are quite likely to have been built up from a collection of motifs taken from very different situations over a considerable number of years,” as Vaughan explained.

I have always sensed in Friedrich’s paintings and drawings, especially those featuring graveyards, ruins, tombs, desolate landscapes, and lonely figures, something of a similar feeling of desolation present in such works as Die Winterreise (The Winter Journey, 1827) by Franz Schubert (1797-1828), which is a cycle of settings of poems by Johann Ludwig Wilhelm Müller (1794-1827), who had taken part in the National Uprising against Napoléon, serving in the Prussian Army in 1813-14. Müller’s Wanderer, who cannot even find rest in the Totenacker (graveyard) among the Totenkränze (wreaths for the dead), because in that Wirtshaus (Wayside Inn) “die Kammern” were “all’besetzt” (all the rooms were occupied), might even be associated with that mysterious Rückenfigur who haunts so many of Friedrich’s paintings. Even in his emptiest landscapes Friedrich was apt to place some kind of marker, perhaps a ruin, a gravestone, a dolmen, a shrine, or a wayside cross to create a special kind of mnemonic atmosphere, while his desolate, snow-covered graveyards with their grave-markers leaning at crazy angles suggest very powerfully the Wirtshaus of Müller’s poetry and Schubert’s Lied.

When considering Friedrich’s hugely impressive legacy (though some of it was lost in the conflagrations of World War II), we have to remember that the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars had a considerable impact on his work, and indeed on German Romanticism as a whole. Even Saxony, in the capital of which the artist had settled, was coerced into an uneasy alliance with France, and the German lands suffered greatly, not just from physical destruction, but from loss of life, as many German states, as vassals of France, had to provide manpower for Napoléon’s forces. The Grande Armée came to spectacular grief in Russia in 1812: of the men who survived to return to the west, some 50,000 were Germans, 20,000 were Poles, and only 35,000 were French. Friedrich himself developed a hatred of all things French, and like many Germans, in the absence of a unified State, saw pan-German identity not only in a shared language, history, and culture, but in the landscape, mediæval ruins, prehistoric tombs, forests, mountains, and great rivers such as the Rhine, Elbe, Main, Neckar, Oder, and Danube. Indeed, in Friedrich’s own time, the landscapes became almost symbols of German cultural identity: he himself referred to “our German sun, moon, and stars, our rocks, trees, and vegetation, our plains, seas, and rivers”, all of which feature powerfully in the artist’s work.

In 1807-8 Friedrich produced a painting, The Cross in the Mountains (Das Kreuz im Gebirge, also called the Tetschen Altar after the residence of its first owners, Franz Anton [1786-1873] and Theresia Anna Maria [1784-1844], Graf and Gräfin von Thun-Hohenstein, the Tetschner Schloß, now called Zámek Děčín, set high above the Elbe in the Czech Republic). It features a rocky mass at the top of which stands a lone Crucifix with everlasting green fir-trees growing on either side: the crucified Christ faces the setting sun, the sky is presented as a rosy glow, and the painting is set in a gilded Gothic frame embellished with palm-fronds and winged cherub-heads (God’s satisfaction with Mankind). At the top of the pointed arch is the Abendstern (Evening Star), proclaiming both Death and Resurrection. In a panel beneath the painting are symbols of the Eucharist (ears of corn and vine branches), and a sunburst with All-Seeing Eye set in a triangle (a symbol of the Trinity). Designed by Friedrich, the lovely frame was made by Christian Gottlieb Kühn (1780-1828). But the daring composition was denounced by the critic, Friedrich Wilhelm Basilius von Ramdohr (1757-1822), who hated the colour, the composition, the tonal contrasts, and more especially the presentation of a landscape-painting as a sacred object. The furore, however, helped to make Friedrich famous.

Also dating from 1807 is the Hünengrab im Schnee (Dolmen in the Snow), in which the Winter, snow, dusk, prehistoric dolmen, and raven (flying immediately to the right of the old decrepit tree on the right) are all associated with Death, while the dying trees are nods to pagan and heroic ancient Germany. Representations of the passage of time, the Seasons, the Times of Day, the Ages of Man, and stages in the evolution of Religion became predominant themes in Friedrich’s work.

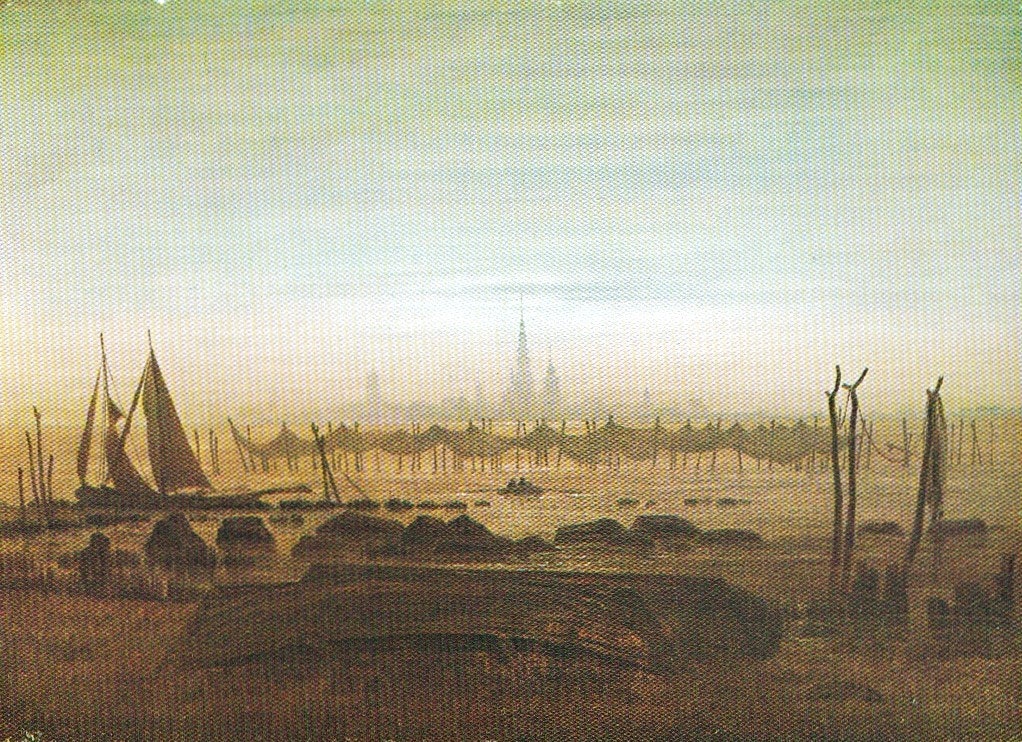

In 1815 Friedrich made a journey to the Baltic where he sketched several motifs, and in 1816-17 he produced the painting known as Greifswald im Monschein (Greifswald in Moonlight) in which the artist’s home town in Pomerania appears in silhouette, but its setting has been completely altered, for Greifswald has been re-sited on the far side of a broad expanse of water signifying Death, threatening the marshy shore that represents earthly existence. The focal point of the painting is the great cathedral of St Nikolai (the 4th-century Bishop of Myra, Patron-Saint of seafarers and merchants), the steeple of which bisects the full moon. This somewhat disconcerting tendency of Friedrich to transport images of real places to different locations, or tamper with reality for the sake of allegory or symbol, recurs in a great many of his paintings.

Zwei Männer in Betrachtung des Mondes (Two Men contemplating the Moon) was painted in 1819-20, the figure on the right with cloak and stick possibly Friedrich himself, and the other August Heinrich (1794-1822), but two later versions of 1824 and c.1825-30 were also made. The two men on the stony path (representing the Path of Life) gaze at the waxing Moon, the low position of which and the rose-mauve light suggest a Spring dusk. The golden halo and startling crescent portray the phenomenon known as Erdschein or Erdlicht (earthshine or earthlight), when, early in the moon’s cycle, sunlight reflected from the earth lights up the shadowed part of the moon and seems to brighten its outer rim. Familiar images from Friedrich’s œuvre, such as the dying oak and the rocky outcrop, recur here.

One of the most touching paintings in the 1972 exhibition was Frau am Fenster (Woman at a Window, another Rückenfigur), painted in Friedrich’s own studio in 1822. It has a tenderness of observation, even in the folds of the woman’s dress. The person depicted was a local Dresden girl, Christine Caroline, née Bommer (1793-1847), Friedrich’s wife, and the view out of the window is across the Elbe to the poplars on the opposite bank, with parts of masts of ships on the river visible. The crossed elements of the window suggest Christian symbolism, and the dark, close interior represents the terrestrial world, so perhaps the distant bank across the water alludes to Paradise? Friedrich had married Caroline in 1818, and the couple had four children, three of whom survived into adulthood. The tender affection so gently expressed in this charming composition shone out from the painting when I first saw it in the Tate, and I have seen it in its home ground several times since then, when it has lost none of its charm or impact .

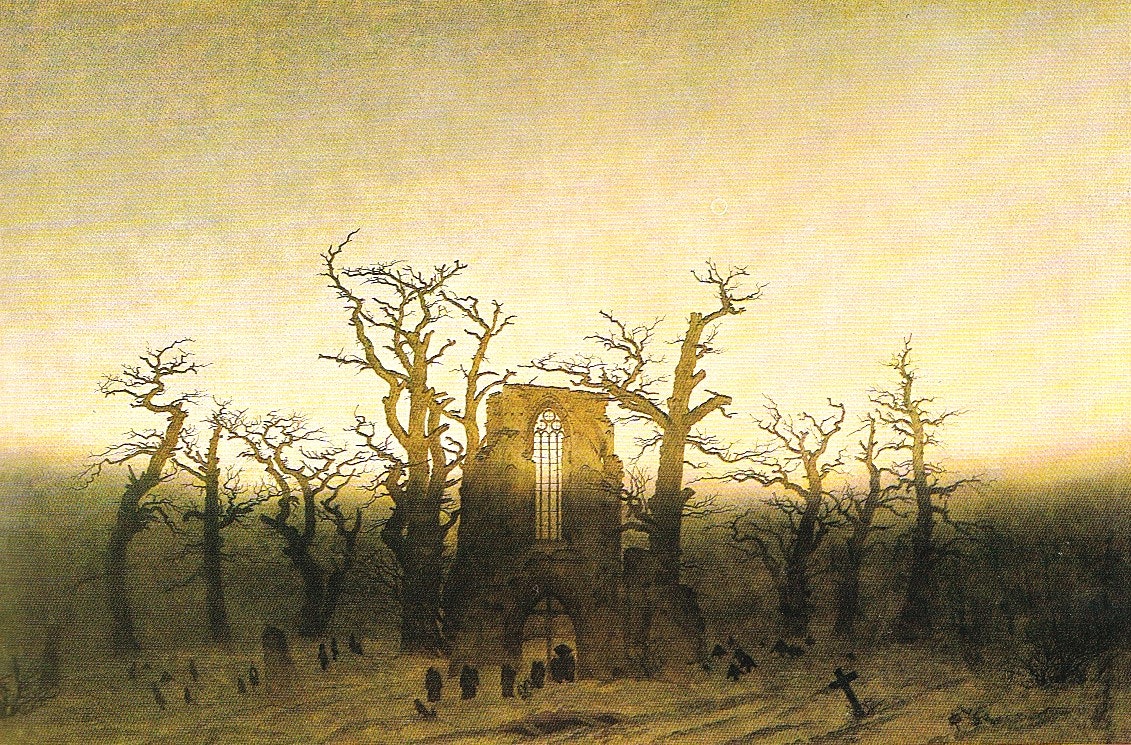

With Abbey in the Oak Wood, of 1809-10, a procession of monks carries a coffin into an abandoned Gothic ruin, and the graveyard lies derelict, its gravestones sunken and slanting at crazy angles, while the bare oaks raise their gnarled branches to the sky as though in supplication, Friedrich had returned to the ruins of Eldena, and, identifying himself as a monk, suggests his own burial in a desolate and lonely place. But perhaps one of his most telling paintings dealing with the finality of Death is found in his Friedhof im Schnee (Cemetery in the Snow), of 1826 or 1827, where the gabled funerary crosses lean with the settling of the graves, and the gravedigger’s tools mark a grave about to be opened. It is a masterly composition, filled with feeling and atmosphere, infinitely true to itself.

I have always believed that C.D. Friedrich’s art could never be anything but German, and its essence is related to other great creations by Germans (in the widest sense), such as Müller and Schubert’s Die Winterreise, the extraordinary Wolf’s Glen scene in Der Freischütz by Friedrich Kind (1768-1843) set to music by Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826), the supernatural operas of Heinrich August Marschner (1795-1861), including Der Vampyr (1828, with a libretto by Wilhelm August Wohlbrück [1795-1848]) and Hans Heiling (1833, with a libretto by Eduard Devrient [1801-77]), and many other works imbued with similar flavourings. There are essentially four levels that are of crucial significance in German Romanticism: the first is that of the miraculous and the supernatural; the second that of folklore connected to the soil and the idea of Heimat which in German means something rather more than mere “home” or “native land”; third, the landscape, with forests, mountains, rivers, and relics of an ancient, pagan past such as burial-mounds, dolmens, and the like; and finally the religious level inhabited by hermits, monks, ruined abbeys, wayside shrines, crucifixes in the hills, and even Christian graveyards lying under the snow, doubling as wayside inns, a last resting-place for the Wanderer, with perhaps an owl or a raven perched on a leaning grave-marker. And the opposing elements of a dark, profane, pagan past and a noble, chivalrous, ordered, Christian future are also present in the music-dramas of Richard Wagner (1813-83), notably Tannhäuser (1845, with later revisions), Lohengrin (1850), and, especially, Parsifal (1882, a miraculous score permeated by the music of the Dresden Amen, which Friedrich would have known well).

There have been several blockbusting exhibitions to mark the 250th anniversary of Friedrich’s birth, and in recent years several marvellous and comprehensive studies of his work have been published, not least the huge two-volume work on his drawings compiled by Christina Grummt and published by Verlag C.H. Beck in Munich, 2011. These wonderful things demonstrate the artists’s sensitivity to the veins of leaves, the complexities of rocks, and the infinite delights to be found in Nature. They show that Friedrich was far more than might be suggested by his disgraceful neglect after his death: he was a towering figure of the 19th century, working at a time when his country was torn apart by wars, uncertainty, faltering beliefs, wobbling allegiances to nationhood when a longing for some kind of unification of the German-speaking lands was seen as a distant ideal, quivering religious doubts, and the tumultuous changes heralded by industrialisation and urbanisation. His world was changing rapidly, and he was racked by inner anxieties, seeking Truth in Nature and Art, finding the Sublime in mountains and mist-shrouded landskips, and expressing desolation, loneliness, and despair in solitariness by darkened sea-shores, snow-covered graveyards, dying gnarled trees hanging over chasms, broken dolmens, and funereal processions among the ruins of the past.

His world, like ours, was tormented by anxieties, longings, regrets, and glimpses of beauties in what had been. Most of all, his vision was that of the solitary individual, freed from organisations such as guilds, schools, Church, and even other people. But it was also, more importantly, an inner freedom, perhaps, unlike those who had emerged from the Enlightenment (or Aufklärung) which had tended towards Abstraction, Theory, and mere Mechanics, and that Freedom was connected with the Spirit, with the wonders of Nature, with Ethics and Education in Morality, recognising the limits of Reason, the importance of personal experience, and the necessity not to ditch what was valuable in Religion, a mistake made by the philosophes, who regarded Religion as mere oppressive Superstition. Friedrich’s fellow-Romantics had a term describing the importance of the primacy of feeling over what is merely seen: it is Erlebniskunst, one of those rather all-embracing German words which means something like the “Art of Experience”. And Friedrich’s art takes us on a journey into even the hardly known experiences of the Inner Being, the Soul.

It is somewhat regrettable that certain of Friedrich’s images, notably the Wanderer, have been appropriated out of context and in dubious taste. The figure occurs on a marketing campaign for Underberg herbal remedies (2021), and Der Spiegel in 1995 adopted the Rückenfigur to represent contemporary Germany surveying its unfortunate recent past, what some have described, with accuracy, as “the paralysing legacy of the Third Reich”. The Brazilian painter, Vik Muniz (b.1961), transformed the Wanderer standing on a pile of cigarette-ash and -butts, contemplating a sea of ashes (1999) representing humanity’s tendency to self-destruct; the American artist, Kehinde Wiley (b.1977) gave his Wanderer (the black professional model and dancer, Babacar Mané) two walking-sticks in his The Prelude (2021); the German Anselm Kiefer (b/1945) drew on images of the sea-shore and the Rückenfigur; another German, Mariele Neudecker (b.1965), produced variations on Friedrich’s images of trees as her inspiration; and for Democrat Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s (b.1989) “Green New Deal”, Jordan Rosenberg designed a T-shirt re-siting a female Wanderer in an American landscape overlooking a great river (2020). An album cover for Sehnsucht (Longing), issued by Decca in 2009, featured the German tenor Jonas Kaufmann (b.1969) in the misty, mountainous, Friedrich landscape, but turned round to face us, and even Angela Merkel (b.1954) appeared in her pantsuit in that familiar setting, high in the clouds. A certain queasiness could be excused when contemplating some of these.

Such tendencies of appropriation can be problematic as well as creative. Reading some of the stuff associated with the exhibitions of Friedrich’s work over the last year or so, one trips over the usual tedious obsessions concerning climate-change, imperialism, post-colonialism, racism, and, of course, the Third Reich, for which poor old C.D.F. could hardly be held responsible as he had pegged out in 1840. I recently heard a senior academic at a Russell Group university confidently claim that Richard Wagner had been a great admirer of Adolf Hitler. I modestly suggested that this was truly extraordinary prescience, as Wagner had died in 1883 and Hitler had only emerged from his mother’s womb in Braunau-am-Inn on 20 April 1889, but such intelligence seemed of no importance to the invincible ignorance of a shut mind.

There is too much stuff churned out about great creative talents of the past that attempts to squeeze them firmly into the concerns of today: the Anglo-German columnist, Alan Posener (b.1949), in a critique in Die Welt of one of the recent exhibitions devoted to Friedrich’s work, slaughtered what he called “infantile didacticism”. Quite so: the obfuscatory indoctrination that now seems to be an essential part of art criticism and essays in exhibition catalogues could well submerge the creations of a huge talent in a Sea of Woke Fog.

Friedrich is shamefully under-represented in the galleries and museums of these islands, a reflection of the excessive adulation of all things French, and the underestimation of and absurdly patronising attitudes to German art that have been so prevalent for far too long. Yet one of the the most outstanding portrait painters of all time was a German from Augsburg, Hans Holbein (1497/8-1543), and nobody possessed of a receptive eye and a receptive æsthetic sense who has visited some of the pilgrimage-churches and abbeys of southern Germany could fail to marvel and delight in the glorious painted ceilings that provide visions of Heaven in those dancing, delicious, light-filled interiors. Things French have been over-rated by the British at the expense of Germany: I have had some of the most memorably delicious meals in the German lands, and some of the very worst in France.

And having seen many exhibitions featuring Friedrich’s work, visited numerous galleries where his paintings are on show, and collected many informative books on his incredibly fine and meticulous drawings and paintings, I can confidently say that I would exchange everything the French Impressionists produced for just two or three Friedrichs. There is more talent and feeling in one exquisite drawing by Friedrich than in all the ugly and grossly over-rated daubs of Renoir et Cie.