This article is taken from the April 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

Monday 28 June, 1813. Thirty-two guests dine around a table to celebrate the King’s birthday at the Royal Academy. The first course — probably turtle soup — is served, champagne flutes refilled. Two glasses clinked together would be those of Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837). Sat side by side, these would-be giants of British art had their inaugural meeting orchestrated by fate, in the form of a seating plan.

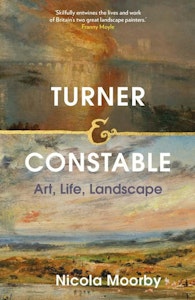

Speculation about the dinner party conversation is one facet of Turner and Constable: Art, Life, Landscape. Art historian and curator Nicola Moorby fuses diverse perspectives in order to preserve the thrill of hagiography without sacrificing integrity to sensationalist accounts.

Early in the book, she declares her aim to give more nuance to binary accounts of two artists structured by blind rivalry. Moorby judges the two artists as if sat side by side rather than face to face, just like their seating plan. Observation affected life, and was then manifested in art, particularly their landscapes.

Accordingly, the book begins with two portraits: a self-portrait by Turner, and a likeness of Constable by Ramsay Richard Reinagle (1775-1862). This pivot in perspective does not deny difference — in fact, the book underlines how the artists were poles apart in temperament, background, beliefs and vision — but facilitates complex interpretation.

One can finish the book and feel equipped to stride confidently into the Tate Modern

Origin stories are immediately foregrounded: Moorby writes about Turner in a Dickensian style in order to establish the urban environment as his context of struggle — the unsanitary conditions of Georgian London and a mother admitted to the horrific Bethlem/Bedlam psychiatric hospital. In contrast, Constable’s life is characterised as an Austenesque novel: halcyon meadowland is the setting for his courting of lifelong love, and eventual wife, Maria.

These two worlds converge at the Royal Academy. Both artists navigated the training and strictures of this institution. Moorby weaves these references throughout; for example, explaining how life-drawing classes educated both artists in narrative emotion and reaction, line, light and shade.

The labourers in Constable’s river pictures are later described as having the physical prowess of classical heroes, “the direct result of years studying musculature in the life class”. Landscape and the media of watercolour and print came low in the pecking order of hierarchies at the Royal Academy, given its preference for historical painting and portraiture. Thus, not only did the artists compete against themselves, but also against institutional biases, further complicating purely biographic accounts of rivalry.

Frequent comparison reveals how each artist navigated these tensions according to their personalities. Turner was a careerist, playing the market for financial gains and status. Aware of the institutional bias against watercolour, he switched to oil in 1796, thereafter establishing his own status as British heir to the European tradition by referencing historical art.

His “meteoric rise” in the Academy saw him become the youngest artist to be elected a full Royal Academician. And so, in 1802, he abandoned his name “William Turner” to become the grand “J.M.W. Turner, RA” — a Romantic reinvention, idealised and distanced from origin. His artworks also became more thrilling: imagination fused with experience traversing the French and Swiss Alps, to seek out the awe-inspiring power of Nature.

In contrast, Constable was fixated on one small corner of England, doggedly determined to forge his own convoluted path through the Royal Academy based on his own rendering of the Truth. Resultant was the timelessly picturesque, moored on the banks of the River Stour. Classical principles — such as the golden ratio, zig-zagging forms, and vertical orientation — injected drama into the otherwise quotidian. Compositionally, The Vale of Dedham (1828) was inspired by Landscape with Hagar and the Angel (1646) by Claude Lorrain (1604/5-1682). His election as a full Royal Academician eventually came in 1829, honouring his vision of England: glorified but quintessentially his own.

Two variants of Romanticism therefore emerge from these divergent artistic temperaments, with national implications to boot. Constable criticised the idealism of paintings by Turner — a “European” attitude debased of artistic origins, as seen in the imaginary mishmash of historical and contemporary elements that coalesce for the frontispiece to Liber Studiorum (1812).

Critics expanded upon the implications for nationhood. Turner’s penchant for yellow — a “foreign” aberration — contrasted to the “silvery freshness” used by Constable to paint indigenous landscapes. Constable himself relayed the pain and pleasure caused by the colouring of Turner’s works, declaring in 1826 that he “is too yellow”. His double-edged reaction ironically casts rivalry as multi-tonal.

Visual analysis is woven with contemporary context. Political turmoil (the Peterloo Massacre, Napoleonic Wars), scientific discoveries and cultural developments passed through and over the British landscape. Vestiges of these national changes are traced in work by both artists, shaped by differing attitudes to modernity.

Representative of this binary is the symbol of the famous hay wain against the steamboat — a hankering for the rural idyll over technological change. Moorby also addresses the historiographical hangover of periodisation, whereby the timing of death has cast Constable as Georgian and Turner as the modern and technological Victorian.

Depictions of nature are the most obvious convergence for the artists. Several environmental foci are addressed in thematic chapters — “Rivers of England”, “Foreign Fields” and “Sea and Sky: New Horizons” — in order to develop initial biographical and contextual ideas.

Moorby adduces scientific publications to show how they inform particular artworks — the halo around the sun known as a “bishop’s ring”, for example, visible in a sketch by Turner, itself testament to the author’s study of the sketchbooks at the Tate. This is a useful complementary to Constable’s practice of “skying”, whereby he applied his leisurely gaze to document clouds in different formations.

Side by side and equally embroiled in nature — in particular, the watery passages of the Stour and Thames — the artists are united as “brother labourers”. The title of this chapter represents the most ambitious historiographical recasting, whereby the final shared decade is presented as a period of friendship and mutual respect.

Legacies are updated, charting a path through contemporary art — light and colour from Turner on Olafur Eliasson (b.1967), and environmental themes in the work of Emma Stibbon (b.1962). One can finish the book and feel equipped to stride confidently into the Tate Modern.

Yet Moorby interrupts our art critic strut to consider the role of institutions in shaping artistic legacy. The National Gallery’s acquisition of Constable’s The Cornfield (1826) made his reputation based on a less challenging work — a “crowd-pleaser” — whilst MoMA has subsequently hailed Turner’s art as style over narrative, a precursor to Rothko.

Moorby mercilessly corrects the Tate’s 1906 presentation of Turner as the forerunner of Impressionism. Instead, she reminds us that it was Constable who received French admiration for the display of The Hay Wain (1821) in the Paris Salon of 1824, whilst pinpointing his originality in applying isolated brushstrokes between unpainted patches of ground. Regrettably, the reader must rely on such snippets of visual analysis, due to the lack of images in the book or their small size when included.

Some shaky propositions are proffered; on occasion these are extended to imagined or assumed meetings between the two artists or pure biographical speculation. Moorby likens Constable’s fascination with clouds to his wife’s tuberculosis: “If only he could breathe health into Maria in the way that he could breathe life into a sketch.” Nevertheless, she nobly acknowledges the patchiness of extant source materials, compensating for the fact that there are more letters for Constable than Turner but vice versa for sketchbooks.

Head cloudy from the landscapes rather than heady from the wine, I leave the dinner table feeling like I still don’t fully know either man. Plentiful gossip has been refreshed by academic rigour, based on a narrative that mobilises binaries to uncover complexity. Just before departure, the embers of drunken disagreements spark up — post-colonial readings, UKIP associations and the controversial Turner Prize — but these are brushed over without wasting space. In this capacity, Moorby is the host who disperses the party before red wine is spilt on the carpet. Professional and elegant but still able to thrill.