This article is taken from the March 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

What do an Irish monsignor, the British ambassador’s valet, an eccentrically named Swiss count, a homosexual SS officer, Mussolini’s mistress, an extensive trove of sadomasochistic literature and the CIA’s James Jesus Angleton all have to do with each other? Espionage: Vatican style, apparently. Yvonnick Denoël’s book, originally published in French in 2021, claims to lift the lid on the Pope’s intelligence services — despite his admission that they don’t really exist. Even so, tales of spying and intrigue orbiting the Holy See are so numerous that an in-depth overview is past due.

Vatican Spies is, alas, as flawed as it is absorbing. Sometimes, Denoël simply gets his facts wrong, as when he asserts that the Order of St Sylvester is the oldest and most prestigious of the Vatican’s honours system. (In fact, it is the youngest and lowest in precedence of the Holy See’s five knightly orders.)

More often he simply misleads the reader with his lack of understanding. His take on Opus Dei is just one example: it is an autonomous self-promoting entity pursuing its own agenda, yet Denoël portrays it as a secret police at the pontiff’s beck and call.

Grievously over-egging the pudding, he claims Opus Dei was instrumental in changing votes at the United Nations over the Algeria question in the late 1950s. Similarly, he can’t resist attributing the 1973 coup against Allende to Opus Dei — members were very much in the plot’s milieu but the group was far from being in the driver’s seat.

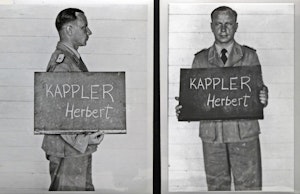

At the same time, it is hard to resist the procession of characters Denoël portrays, whether they be rogues or heroes. The action naturally ramps up in the Second World War, as Mussolini is ousted, Italian fascism collapses, and the Germans occupy Rome. Within a month, Hitler dispatched SS Obersturmbannführer Herbert Kappler to head the Nazi security apparatus in the Eternal City.

The German met his nemesis in Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty, a charm-laden cleric from neutral Ireland who organised a network hiding, housing and feeding Jews, escaped prisoners of war, shot-down Allied pilots and others deemed undesirable by the Nazi occupiers.

With currency in short supply, Denoël reports, the Vatican bank lent millions to the British Embassy to the Holy See to help the Irish monsignor’s work, aided by John May, the crafty valet to Ambassador D’Arcy Osborne (later 12th Duke of Leeds), and the Swiss diplomat Count Sarsfield Salazar — a name worthy of J.K. Rowling.

Denoël fails to appreciate that spying at the Vatican has greater mystique than actual substance

At the end of September 1943, Kappler summoned the Chief Rabbi of Rome, Israel Zolli, and other leaders of the Jewish community and pledged (mendaciously) to keep their people safe if they would surrender 50kg of gold. Even Zolli’s best efforts could not produce the demanded amount without assistance from O’Flaherty and the Church. Pope Pius XII himself suggested which church gold might be melted down to reach the demanded amount (though he pedantically described the church’s contribution as a “loan”).

In the face of Kappler’s effective counter-intelligence programme, O’Flaherty’s network was forced to shift tactics and operations constantly but responded with vigour. Though cash-strapped, valet John May made a fair assessment of the uprightness of Italian policemen and decided it was worth the bribe money to obtain the police orders of the day in order to keep at least a few hours ahead of the authorities.

Denoël is convincing on the utility of the longstanding tradition of the diplomatic bag, as well as its subversion. With normal postal services interrupted, Swiss diplomats offered to act as the channel for the Vatican’s correspondence abroad. Later in the war, Britain likewise helped the Church keep in touch with dioceses in the British dominions and colonies.

The US government kindly offered to help with the Americas: the FBI did not resist the opportunity to illicitly open and copy all the messages, leaving the possibility of a rich archive of Vatican diplomatic correspondence somewhere in Washington yet to be dredged by researchers.

It wasn’t just state actors who got involved in the church’s mail: the Italian insurance firm Generali found it useful to send files to its subsidiaries abroad via the Vatican’s diplomatic bag. If there is one solid lesson from this book it is that having important friends high up in the Vatican is good for business — in times of war, all the more so.

Post-war Rome is also well depicted here. American masterspy James Jesus Angleton was tasked with hunting down Germans who might be useful to the American intelligence services and exfiltrating them across the Atlantic. This meant concealing one SS officer from the new Italian authorities, for which the former apartment of one of Mussolini’s mistresses did the trick as a hiding place.

Holed up for weeks, the bored SS man explored the palatial flat’s library and discovered an extensive trove of sadomasochistic literature — but Angleton’s potential asset was homosexual and not himself intrigued by that particular diversion.

Chief Rabbi Zolli, meanwhile, was so impressed by Pius XII’s wartime conduct that he converted to Catholicism after the war and took “Eugenio” (the pontiff’s pre-regnal name) as his baptismal name. Kappler was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment, though many argued that he deserved death for organising the massacre in the Ardeatine caves. Monsignor O’Flaherty didn’t let Kappler escape so easily: for years this formidable Irishman was the only visitor the SS man received in prison. In 1959, O’Flaherty baptised the German in his prison chapel and received him into the Catholic church.

The further Denoël gets from the war, the weaker and more credulous he becomes. Later chapters cover the Vatican’s efforts to send undercover priests to tend to the remaining flock in the USSR (and particularly Soviet Ukraine), infiltration by Eastern Bloc services (whose capabilities Denoël overestimates), and the many dodgy financial and political dealings of 1970s Italy. Alan McKay’s translation is sometimes irritating: the PCI — Italy’s communist party — is consistently referred to here as the “ICP”, while intelligence services of whichever national origin are honoured with their autochthonous abbreviations.

Overall Denoël fails to appreciate that spying at the Vatican has greater mystique than actual substance. For over a century, the preponderance of the Holy See’s business has unsurprisingly been ecclesiastical in nature, rather than attempting to steer the course of geopolitics. A more conscientious writer on the same subject, Professor David Alvarez, has pointed out that foreign governments spying on the Vatican often knew much more about the real state of world affairs than the clerical state they sought to spy on. The careful reader will enjoy this book but should take many of the author’s assertions with a pinch of salt.