This article is taken from the March 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

One of the many perks of being Arts minister is selecting works from the Government Art Collection. All ministers are allowed to borrow a few pieces for their offices, but there is special licence — and additional responsibility — when making a selection as arts minister. The visitors to his or her office are likely to have a keener interest, and a more critical eye, to cast over the pieces chosen. Though I benefitted from excellent recommendations by successive directors of the Government Art Collection, Penny Johnson and Eliza Gluckman, I felt it important to select a few which reflected my own tastes.

Hewn from Northumbrian mining stock, I have long enjoyed the work of the Ashington Group, immortalised in Lee Hall’s play, The Pitmen Painters. Alas, the Government Art Collection has not yet acquired any of their paintings (though perhaps the new culture secretary can put that right: I was pleased to read that she asked on her own visit to pick artworks, “Have you got anything with miners?”). But another group of working-class artists whose work I admired was represented.

The East London Group, more than 30 mostly working-class artists whose centre of gravity had an E3 — Bow — postcode, blazed brightly but briefly in the 1920s and 30s, then largely faded from view. They honed their skills at evening classes taught by John Cooper, a Lancashire-born, Yorkshire-bred graduate of Leeds and Bradford art schools, then the Slade. Like Robert Lyon with the Pitmen Painters, Cooper’s classes were an experiment in one of London’s most deprived areas, helping to unlock the creative talents of window-cleaners, park-keepers, engine-drivers and other working men and women.

Walter Steggles — who worked in a shipwrights’ drawing office from the age of 14 — recalled how members “would pay a penny a week for lessons. If they could not pay, they would be let in anyway”. Cooper arranged trips to galleries and the Proms, and persuaded artists such as Walter Sickert to come and speak: he visited more than once, talking long into the night.

❂

As the East London Art Club, Cooper and his protégés exhibited at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the winter of 1928. Their exhibition, hailed by the Studio as “little short of sensational”, convinced Charles Aitken, director of the National Gallery, Millbank (now Tate Britain), to give them their own show there. This was accompanied by eight successful exhibitions at the West End gallery, Alex Reid & Lefèvre, between 1929 and 1936.

From the outset, the group won admirers in high quarters. Arnold Bennett, Samuel Courtauld and Sir Joseph Duveen supported their Whitechapel exhibition. Politicians from George Lansbury to Lady Cynthia Mosley championed them. Ramsay MacDonald attended one of their exhibitions as prime minister, hailing it as “Labour’s own art show” — but didn’t buy anything. Those who did become early collectors included Lord Berners, Henry Lamb, Lady Emerald Cunard, Aldous Huxley and J.B. Priestley.

Perhaps their apogee came in 1936, at the 20th Venice Biennale. This was the first time the British Council had responsibility for organising the British Pavilion, and the UK did not exhibit officially both because of this organisational upheaval and in protest at Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia. But a selection of modern British paintings were sent, with Elwin Hawthorne and Walter Steggles from the East London Group amongst the 27 artists featured alongside Duncan Grant, Barbara Hepworth, John Nash, Augustus John and Walter Sickert.

❂

It is surprising, then, that the Group should have faded from memory so quickly — certainly compared to the Camden Town Group, which also drew inspiration from Sickert and was formed a few years earlier. The interruption of the Second World War and Cooper’s death in 1943, at the age of just 48, did not help. Some of the group expressed an interest in serving as war artists, but none were chosen. Unable to abandon their jobs and families, only a handful continued to work as artists, and its members fell out of touch.

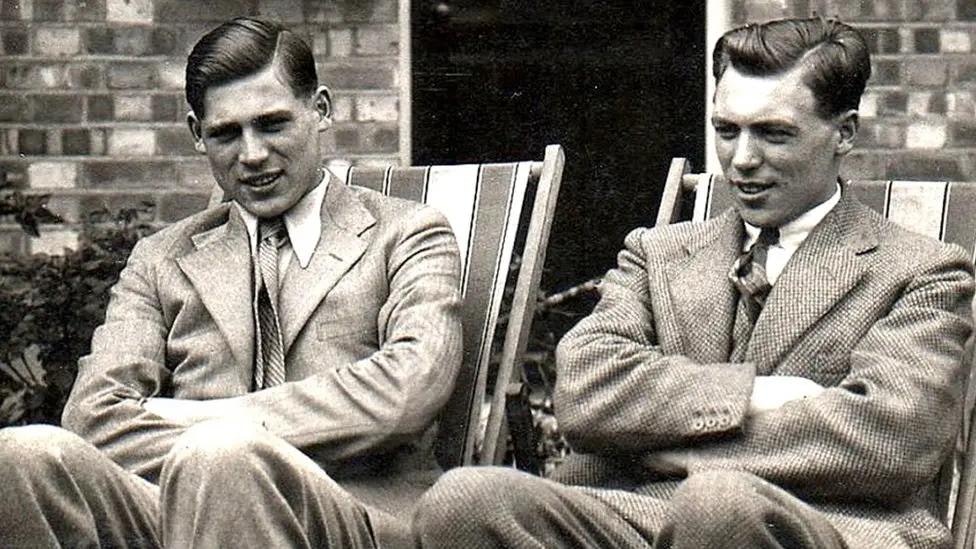

A BBC article in 2017 profiled “The famed painters who vanished into obscurity”. But recent years have seen a resurgence of interest, thanks in large part to David Buckman’s diligent survey, From Bow to Biennale, published in 2012, and to the heart-warming energy of Alan Waltham, whose wife Janeta is the niece of two of the group’s core members: the brothers Walter and Harold Steggles. After finding themselves custodians of Uncle Wally’s papers, Alan has spent the past 16 years drawing attention to the group, sharing their work online and staging new exhibitions.

In one of his lectures to the group, Sickert told them that paintings should have a “Look here” quality. Perhaps that is even truer for the weary eyes of the doom-scrolling generation. The images Alan shared online certainly made me look, and I have been hooked ever since. I travelled to exhibitions at the Nunnery Gallery in Bow, and at Southampton City Art Gallery in 2017. To my delight, a new one, centred on Walter and Harold, Brothers in Art, opened at the Beecroft Gallery in Southend the very month I was appointed arts minister. I dragged my new colleagues from the department along, recruiting some further fans.

Sadly, neither of the Steggles brothers have works in the Government Art Collection. But two East London Group artists — Sam Carter and Phyllis Bray, who married Cooper — are both represented. I was delighted to have Carter’s fine painting of St. Anne’s, Soho in my office throughout my time as Minister and Buckman’s book on my coffee table.

❂

This enthusiasm proved the danger: my private secretary Rebecca was a keen watcher of online auctions, and would tempt me with links when pieces came up for sale. In meetings with gallerists and curators, I was sometimes asked, “Do you collect?” Despite my personal and professional interest, the question still seemed an alien one: I had amassed plenty of posters and prints, but it had never crossed my mind to buy an original work of art.

Like fine wine and opera, the voluble passion of the already-initiated made me nervous about trying to play catch-up, and I assumed that I wouldn’t be able to afford to do so anyway — even the Affordable Art Fair seemed beyond my budget. In fact, brilliant schemes like Own Art, which offers interest-free loans to help people buy works from living artists, make it more attainable. So it seemed entirely appropriate to use part of my severance pay after the general election brought to an end my time as arts minister, on becoming an art owner.

Thus it was that, last October, I bought at auction Walter Steggles’s Essex Landscape with Pollards, one of the works I’d seen at the Beecroft. I took the baby step of bidding online, sitting quietly in front of the computer hitting “refresh” rather than in an auction room surrounded by others who knew what they were doing. Seeing the banner change from red to green prompts a mixture of elation, accomplishment, panic and anti-climax as the screen moves on to the next lot.

The work I bought was painted in 1932 and shown at the Lefèvre exhibition that year. It was bought as a Christmas present for the ten-year-old Mary Soames, youngest daughter of Winston Churchill, by her nanny, Maryott Whyte. Mary kept it for the rest of her life, then Alan and Janeta bought it from the sale of her effects at Sotheby’s in 2014.

This Christmas present is one of many surprising links between the Churchills and the East London Group. Lord Ivor Spencer-Churchill, a painter and younger son of the 9th Duke of Marlborough, followed the group’s progress and came to its private views.

Sir Edward Marsh, Churchill’s longstanding private secretary, was a keen collector and patron of the arts. He served as chairman of the Contemporary Art Society, which bought a number of Steggles’s works, and invited Walter and Harold to his art-bedecked apartment at Gray’s Inn many times. Similarly, the brothers were invited on several occasions to at-home and open studio events by John Churchill, a painter and nephew of the wartime premier, who admired the East London Group.

So it is not surprising that the Churchills’ nanny should have admired Walter Steggles’s painting — especially as she was not just an employee, but a relative. She came to work for the Churchills after the traumatic death of their daughter Marigold. Born four days after the Armistice in 1918, the two-year-old Marigold took ill on a trip to Broadstairs. Her young, French nanny did not recognise that her sore throat had turned to septicaemia; her distraught parents rushed to be with her, and were at her side when her short life ended.

Understandably wary of nannies, Clementine turned to her cousin Maryott, a trained Norland nurse. Known as “Moppet”, she was a granddaughter of the Earl of Airlie, but her mother’s improvident marriage meant she and her siblings had to earn their living. At one of Mary’s birthdays, Winston wrote to Clemmie admiringly that Maryott “always thinks of the most enchanting gifts”.

But if Steggles’s painting was wrapped under the tree in 1932, it had a narrow escape — the Christmas fir, decorated with white candles, caught fire “and was ablaze in mere seconds”. Whilst others panicked, Maryott “was absolutely in her element”, and extinguished the flames.

❂

Sadly, other works by the East London Group have been lost to the flames of misfortune. After the death of Albert Turpin — a window cleaner and committed socialist who stood up to the fascists at Cable Street and served as Mayor of Bethnal Green — in 1964, his widow cleared out their shed and burned most of his paintings.

The Steggles’s family home in Romford was the victim of a German bomb in 1940, and a number of Walter’s paintings were destroyed; the Lefèvre gallery was also hit in the Blitz, with papers relating to the group lost. Of the more than 700 East London Group paintings exhibited in the 1930s, just 150 have been located by Waltham. He currently has no information about ten members of the Group, an area which remains ripe for study.

Walter Steggles was the last active member of the group, painting well into his eighties. A bachelor, he and his mother moved frequently, spending periods in Cookham (where they knew Stanley Spencer), Norfolk and Wiltshire, where he died in 1997.

He remained amused by the many reasons people bought his work. Someone had once bought one because their own name was Steggles; another purchased one from Lefèvre because she had lived in the street depicted. “Later, Lefèvre tried to buy it back because it had greatly risen in value, but she would not sell,” he recounted with pride. I hope he would have enjoyed the reasons for my purchase as much as I enjoy having it.