Abundance.

It’s a word you still occasionally hear. Peter Diamandis, founder of X Prize, is very keen on it.

But then, he is the personification of a particular West Coast US mindset: Elon-adjacent, Bitcoin-curious, AI-boosting. (He has also written a book on how to reverse aging.)

Diamandis is definitely not aligned with the cultural vibe here in Northern Europe, where efficiency is treasured and waste is beyond the pale.

But it wasn’t always that way. Decades of rising living standards in the second half of the 20th century created expectations around automation and free time.

Public discourse around nuclear power in the 1950s and 1960s—exemplified in Heinz Haber’s 1957 book and Disneyland episode “Our Friend the Atom” —focused on a future of abundant energy.

Nuclear energy was supposed to offer electricity too cheap to meter.

Across the capitalist world, and in the Eastern Bloc, too, the dividend of technology was supposed to be one of plenty.

But now we seem to have given up on the idea.

So much of the growth in productivity in recent decades has come from optimizing, not from augmenting.

Marginal gains, eked out from yield management and supply chain optimization—not reactors full of glowing rods of uranium dumping megajoules into the economy.

Even in California, where abundance still zhuzhes up the discourse, much of the tech industry’s reality focuses on squeezing out extra value.

And so today, we have taxis you can’t book at busy times—unless you cough up for surge pricing.

Flights that are always full, with tickets that shoot up in price on desirable days, and the risk of being bumped off if there are too few no-shows.

Restaurants and hotels are fully booked, meaning you can’t walk in on a whim.

Dynamic pricing for Oasis tickets.

Even my local swimming pool wants people to pre-book their slots. (I’m looking right now: there are 3 more spaces available for lane swimming tomorrow at 9 AM. Book now to avoid disappointment.)

Instead of abundance, we have an economy that’s only just short of scarcity.

It wasn’t always like that.

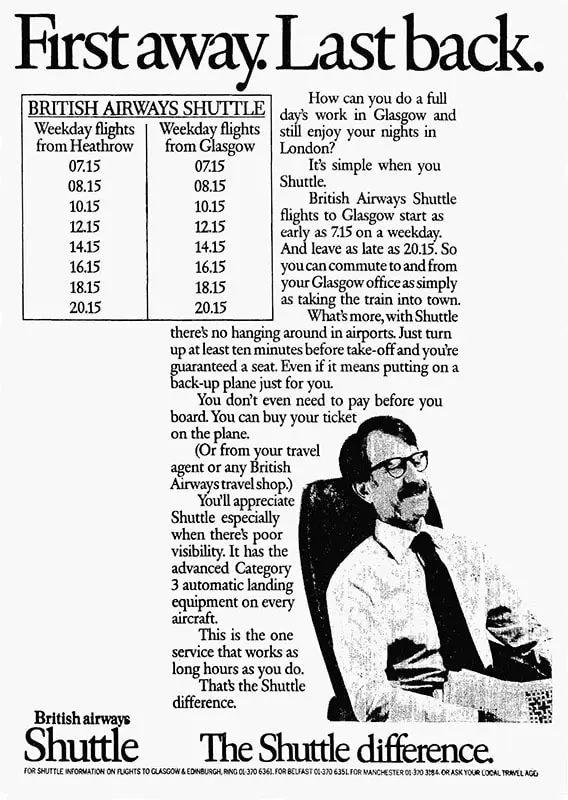

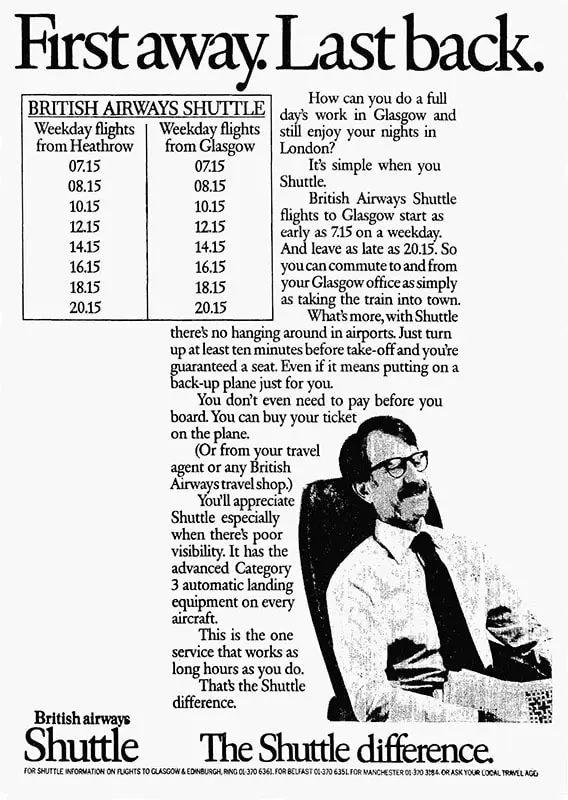

You used to be able to turn up at Heathrow and pay on board for a flight. BA would have extra planes on standby in case there were more passengers than expected.

Pre-booking trains, hotels, restaurants, and taxis was not the norm.

I think we’ve gotten so used to this that we’ve forgotten spontaneity. But I don’t think we’ve fully culturally adjusted to it, either.

Because a hyper-optimized economy doesn’t feel great.

People don’t like surge pricing. At all.

You can argue all you like that it’s about incentivising extra supply or ensuring availability. While these are true, it still feels like rationing, for the very good reason that it is rationing.

People also don’t like services falling over as soon as there’s extra demand or poor weather, because the systems have no resilience or redundancy built in.

Maybe it’s for the best. People don’t like high prices or inefficiency either, and (in this country, at least) they don’t like global warming.

It’s a big cultural shift, and one I don’t think is commented on enough.

It’s a huge economic and environmental shift, too.

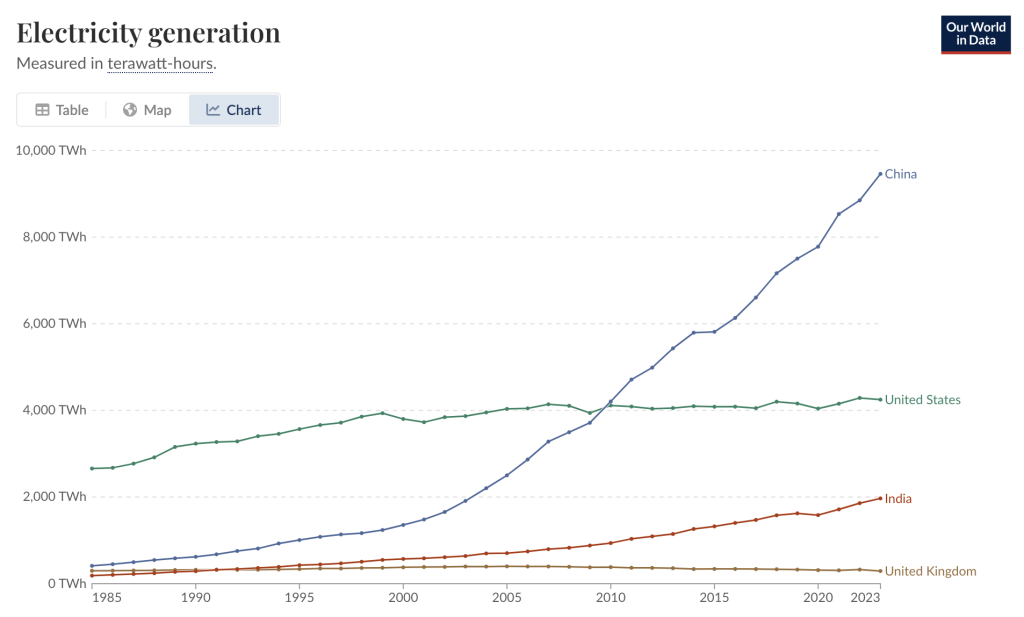

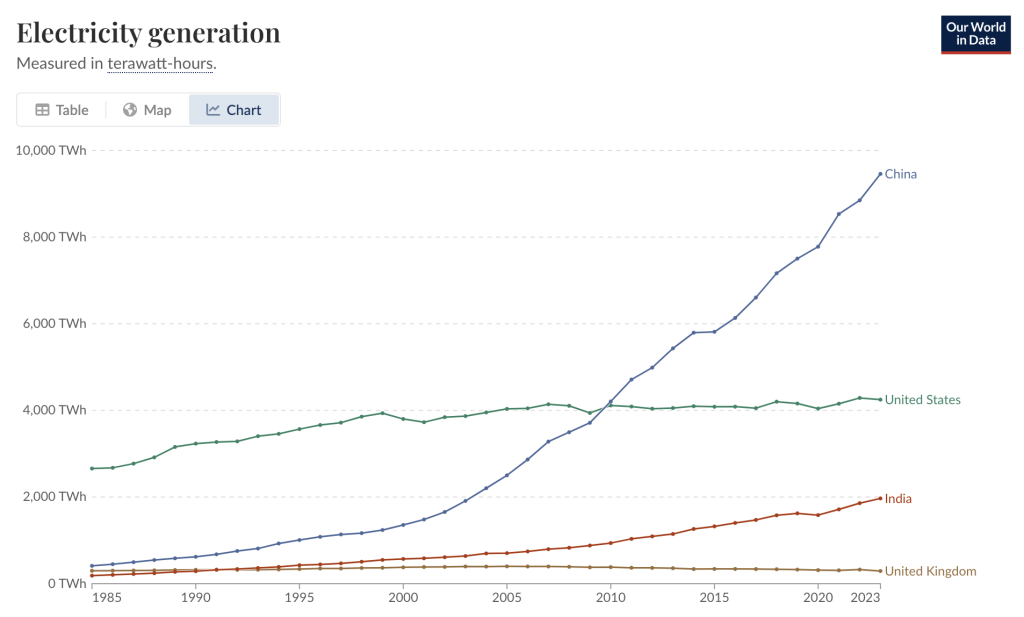

You can see it right here:

British electricity generation is down by about a quarter of its 2003 peak, while China’s has quintupled.

I’m a product of the Northern European cultural environment. I’m not a big fan of waste, and I certainly don’t want to ruin the planet.

But a little bit of slack in the system—some space for spontaneity—sounds nice.

And I’d like it if we could get that back.