With President Donald Trump’s announcement of “Liberation Day” trade tariffs Wednesday, the world appears to have crossed into a new era.

For nearly a century, the international economy has been driven by the seemingly unstoppable force of globalization, built on the premise that free trade benefits all.

Those days seem to be over.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

After nearly a century of ever-freer trade, an era has ended with Donald Trump’s imposition of trade tariffs on U.S. imports, as other nations get ready to retaliate. What clues do the vagaries of trade policy in the past offer us?

Dozens of new tariffs on U.S. imports, including a 54% tax on Chinese products and a 20% levy on goods made in the European Union, have led leaders around the world to lament an apparent return to the protectionism of centuries past.

Indeed, the world has swung from free trade to protectionism and back again before. Yet it has never seen a moment quite like this one.

“Countries have reintroduced tariffs in the past,” says Fredrik Erixon, director of the European Centre for International Political Economy in Brussels. “What is rare is that countries use new programs of protectionism to basically hurt their own economy.”

What are the roots of free trade?

Economists have been advocating for free trade as far back as the 16th century in imperial Spain. Yet it was not until the 18th century that such ideas began to gain traction.

Until then, mercantilist thinking had led European nations to prioritize the accumulation of wealth, exporting as much as possible and importing as little as possible. Adam Smith and later David Ricardo showed that, in fact, freer trade creates more prosperity for both partners by opening doors to cheaper goods and allowing nations to specialize in sectors where they enjoy a comparative advantage.

The industrial revolution meant Europe and North America had more goods to trade than ever before, as well as railways and steam engines to carry them. A shift toward free trade took place during the 19th century, sometimes called the “first age of globalization,” when tariffs on grain were lifted, and new trade agreements spread across Europe.

Some such agreements were imposed, as when Britain and its militarily victorious allies obliged the Chinese government to open its market to free trade.

Yet protectionism has often made a comeback during moments of crisis or uncertainty. The impetus for free trade slowed in the second half of the 19th century, first by an economic depression in the 1870s, and came to a halt with the outbreak of World War I.

The end of World War II brought a newfound commitment to free trade and global cooperation in Europe and the United States – a commitment that has lasted to a greater or lesser degree until now.

What is the case for protectionism?

Free trade has long had its critics.

German thinker Friedrich List responded to Adam Smith by arguing that some protective measures are needed to allow less-advanced nations to shelter nascent industries until they can compete internationally. Most advanced economies matured behind the shelter of protectionist policies.

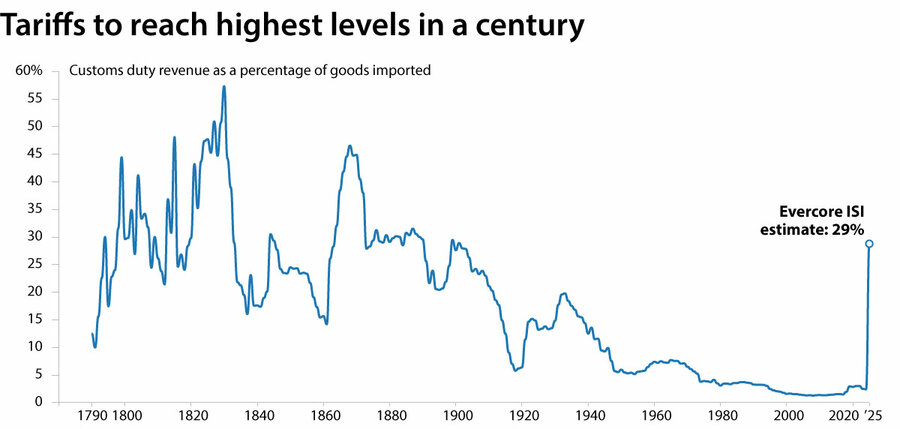

During the Great Depression, the U.S. passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which raised tariffs to their highest level in the past century – until Mr. Trump’s new policy.

Meant to shield the struggling American economy, the heavy tariffs backfired. They sparked a trade war and helped spread America’s economic depression to the rest of the world. The value of international trade fell by two-thirds between 1929 and 1934.

Still, after World War II, many emerging economies, especially in Latin America and Asia, used tariffs to shelter their young industries, just as Europe and North America had done before them. If emerging economies imported all their manufactured goods, went the logic, their own industrial sectors would never develop.

By the mid-1980s, protectionism had gone out of vogue and a new age of globalization arrived.

Why has faith in free trade faltered now?

Global trade has exploded since the 1980s, as countries around the world have opened and deregulated their economies. But there is a growing sense that what some have called the hyperglobalization of recent decades may have gone too far, without protecting those who lose out from the process.

While the U.S. has specialized in high-tech sectors, manufacturing has largely moved to other countries such as Mexico and China. While that has economic benefits for the nations involved, it does not mean that former factory workers in America have gotten new jobs in the tech sector, says Kevin Gallagher, director of the Global Development Policy Center at Boston University.

In the original economic theory, “some transfer should happen from the gains from the winners to the losers,” says Dr. Gallagher, so that these workers can find new jobs through training and education. By failing to provide such paths, he says, both U.S. political parties have helped pave the way for the current backlash.

Over the past decade, governments have been taking more and more active roles in shaping their nations’ industrial policy; trade restrictions increased by 500% worldwide between 2015 and 2023. Yet these measures, largely meant to boost specific industries and domestic competitiveness, pale in comparison with the Liberation Day tariffs.

What does this mean for the current moment?

Economists such as Dani Rodrik, a professor at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, have argued that tariffs can be useful when applied moderately and in support of specific policy goals. They also stress that they are not a panacea for economic revival, and that when used indiscriminately, they can wreak havoc.

Leaders in every economic Cabinet around the world are now being forced to decide how to respond to Mr. Trump.

“We built a postwar global multilateral economic system around the United States, and so there isn’t a global infrastructure to try to even mitigate this problem,” says Dr. Gallagher. “It’s every country for itself.”

Fortunately for some, he says, the U.S. economy is not as dominant as it was in the 1930s, so the global impact may be more measured than some fear.