This article is taken from the May 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

In the recent film The Critic, adapted from Anthony Quinn’s novel Curtain Call, the eponymous theatre reviewer Jimmy Erskine, as played by Ian McKellen, cannot be regarded as a shining example of his profession. Not only is Erskine a harsh denigrator of what he sees as untruthful acting on stage, tearing into hapless thespians in his regular column in the Daily Chronicle, but his extracurricular activities include furtive al fresco sex with anonymous men, blackmail and, when the occasion eventually calls for it, murder. By the time that the conniving critic gets his comeuppance, few will feel great sympathy for him.

All the same, Erskine — a character based on the Sunday Times theatre reviewer James Agate — is allowed some insightful and witty Patrick Marber-scripted lines about what the role and function of a critic should be. Erskine initially declares that, like many writers, he is merely there to divert his readers: “I have a duty: to entertain the audience,” he scoffs. Yet as the story darkens, the protagonist acquires near-Shakespearean self-awareness about his situation. Erskine eventually observes, “The critic must be cold and perfectly alone. Only the great are remembered.”

The Critic failed at the box office, proving that period dramas revolving around homicidal theatre critics have a limited audience. Yet it also managed to make some relevant observations about what, exactly, anyone who goes expectantly into a first-night audience should intend to offer their readers.

✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍

Is it a critic’s duty to be an everyman, an easily impressed — or easily bored — observer who will write up their thousand or so words from the perspective of the average theatregoer? Should they be expected to be a Bamber Gascoigne-esque sage, someone who has an encyclopaedic knowledge not only of the plays themselves but of the oeuvre of the director, actors, designers and even the understudies, if required?

Or should the theatre critic be something else entirely — not an innocent, not a cynic, but a writer who is able to take the perspective of an informed and insightful friend to his or her readers and advise them, without condescension or vainglory, whether they should spend their time, money and effort seeing that particular play at that particular theatre?

Theatre criticism is as old as the dramatic art itself. Aristotle’s Poetics, written the best part of two and a half millennia ago, set out the basic requirements for what tragedy and comedy should be, and woe betide any Apollo-come-lately who was unable to fulfil such necessary demands. Yet even before then, there must have been some basic form of dramatic criticism.

A century earlier, someone must have seen a performance of Oedipus Rex and somehow communicated to their friends and family what its strengths were. (“It’s blindingly good!”) We know that it won second prize in a festival to honour the god Dionysus but have no idea what beat it. Presumably, that play is now lost, along with the vast majority of all ancient drama, however well received it was at the time.

Writers such as Hazlitt and Leigh Hunt made theatre criticism a respected branch of the literary arts in the 19th century, but I’m more interested in the views of those who we’ve long since forgotten about. When Hamlet was first performed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men in 1600 or so, starring Richard Burbage as the vengeful Dane and supposedly with Shakespeare himself as the Ghost, there must have been someone standing in the Globe, probably on his own, who walked away afterwards and communicated his considered thoughts to his friends and neighbours.

“Yes, it was reasonable … didn’t like it as much as Richard II … Burbage up to his old tricks again, wish he’d stop bellowing … good ending, mind.” In that anonymous observer, as lost to history as the forgotten works of the Greek tragedians, we see the immediacy and impact of theatre criticism: the right to offer an opinion and to have that opinion taken seriously.

✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍

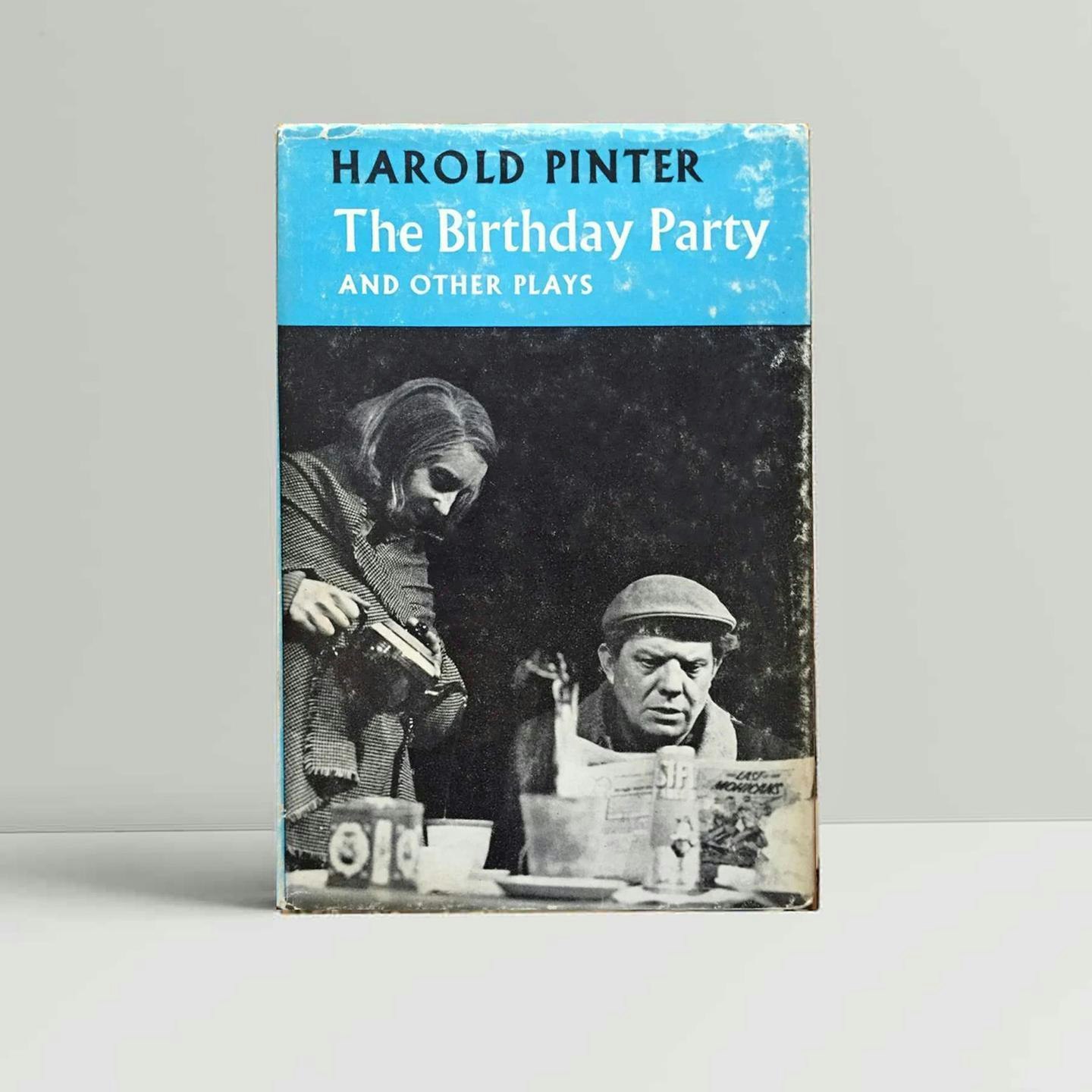

The 20th century was where the critic-as-celebrity flourished. The likes of Agate and his successor at the Sunday Times, Harold Hobson, were sufficiently influential to make or break a play or production. If Hobson had not championed Harold Pinter’s debut, The Birthday Party, it is likely that Pinter would have been forgotten and one of the most remarkable careers in 20th century playwrighting would have ended before it began.

Nobody, however, could hold a candle to the greatest and most glamorous critic-celebrity, the Observer’s Kenneth Tynan. His middle name was “Peacock”, and appropriately enough, Tynan’s epigram-laden, meticulously constructed reviews glittered and shone in the relative murk of the rest of the newspaper. To read his writing today is to be transported back to another, more exciting era, one of legendary actors and mighty playwrights and off-stage (occasionally on-stage) feuds of ferocious tempestuousness.

Tynan was often as wrong as he was right. He launched John Osborne’s career in 1956, famously declaring, “I doubt if I could love anyone who did not wish to see Look Back in Anger,” only to watch Osborne reject his patronage and slide into increasingly worthless self-parody. He sneered at the great Terence Rattigan as a middle-class anachronism, asking him faux-innocently, “I really don’t know why you put up with me. There must be moments when you wonder whether it’s all worthwhile.”

His off-stage antics, which included flagellation, cross-dressing and a self-administered vodka enema — all described with Tynanian flair in his diaries — saw him sent down to posterity as a pervert and roué. Yet it was his skill and accessibility as a critic that made him legendary, rather than his bedroom behavior. I doubt I could love anyone who did not wish to read Kenneth Tynan, even today.

✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍

There have been outstanding critics who have followed Tynan — the Guardian’s Michael Billington, in particular but also the Observer’s Susannah Clapp, the Sunday Times’s John Peter and the Times’s Benedict Nightingale. These critics may have been white middle-class men and women of a certain age, but what they brought (and, in Clapp’s case, still bring) to their writing is a lifetime of love and appreciation of the theatre.

They know, as all actors and directors do, that to review a dramatic performance is not to consider a finished article, as one does with a film, album or book, but to watch something that changes subtly and inexorably with every new audience, every laugh that doesn’t land or cough that disrupts a tragic moment.

They understood, too, that a critic for a well-known title has a responsibility to any number of interested parties, but most of all to themselves. “To thine own self, be true,” that old windbag Polonius declares in Hamlet. Well, the same is true of any theatre critic. Pander to taste, fashion or expectation, and you’ve lost before you began. Write well, accessibly and engagingly, and your own audience will trust you.

✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍

It’s the greatest honour of my professional life to date to have become The Critic’s theatre critic. I can only hope that I will build on the excellent work of my predecessor, Anne McElvoy, and summon up a suitably Tynanian spirit in my own writing, although hopefully without the vodka enemas.

The opportunity to head to the stalls or royal circle once a month — and hopefully more often, if schedules and online publication allow it — is a giddily exciting one, and I intend to take as much effort in seeking out less-considered plays in fringe theatres that will, I hope, appeal to Critic readers as in attending the latest star-studded West End opening. I’ve taken up this position at a time when contemporary theatre is in a dire position, and contemporary theatre criticism doesn’t seem to have much of an idea how to deal with it, either.

When Rufus Norris became artistic director of the National Theatre — the most important job in British theatre — in 2015, succeeding Nicholas Hytner, I was not optimistic. Norris had directed some excellent productions before, including a fine Cabaret with Anna Maxwell Martin and a much-praised adaptation of Festen, but he seemed like a director instinctively uncomfortable with the concept of the theatrical canon. Norris favoured new work, adaptations and diverse, self-consciously “energetic” productions.

After a promising opening to his regime, which included stagings of Farquhar’s The Beaux Stratagem and a new version of The Threepenny Opera, the National was torn apart, firstly by Brexit, then by the forced closure occasioned by Covid and finally by Norris’s apparent disregard for (or ignorance of) any drama written before the 20th century.

By the time that a high-energy, cross-dressing The Importance of Being Earnest was staged last year, starring Ncuti Gatwa, it became increasingly clear that Norris had no interest in the work of his estimable predecessors Hytner, Richard Eyre, Peter Hall and even the once-maligned Trevor Nunn, all of whom specialised in reviving the classical canon with the best actors in the country. New writing replaced old, and the fact that it often wasn’t very good seemed irrelevant. Diversity and “relatability” replaced dramatic and theatrical integrity. Many directors and actors who had thrived under previous regimes quietly stayed away.

✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍

Norris is leaving after a decade in the post, to be replaced by Indhu Rubasingham, late of the Kiln, and it looks likely that the National’s programming will continue to follow a similar path: a heavy emphasis on new writing, which she has largely specialised in, with plays by the pale, male and stale confined to the theatre’s library, at best.

So we must look elsewhere for a representative overview of British theatre today, and the omens are not promising. The West End has become a repository of expensive star vehicles, following the Broadway model, where you can charge hundreds of dollars in exchange for a couple of hours in the company of your favourite movie or television actors: the play is almost irrelevant.

Sometimes, this works well (Tom Hiddleston and Hayley Atwell won rave reviews for Jamie Lloyd’s recent Much Ado About Nothing) and sometimes this flops: Sigourney Weaver’s Prospero (Prospera?) in Lloyd’s staging of The Tempest was so poorly reviewed that you have to give the otherwise estimable Weaver credit for not simply leaving London altogether after the damning criticism.

Either way, the market for A-list stars, live and a few feet away from you, shows no signs of ending. As I write, Ewan McGregor and Elizabeth Debicki are about to open in Lila Raicek’s Ibsen update My Master Builder, the great John Lithgow is transferring his triumphant Royal Court performance as Roald Dahl in Giant to the West End, and Gary Oldman bucks the London-centric trend by giving a one-man, self-directed performance in Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape in York. It could be peerless; it could be terrible: you never know with this most quixotic, and fascinating, of actors.

Oldman’s decision to head North, rather than to W1, is stirringly unusual. British theatre is, of course, dominated by groupthink, both geographically and politically. Whilst the rest of society breathes a sigh of relief at having to abandon the false compromises and mental gymnastics necessitated by the rapidly fading credo of wokery, this firmly left-leaning profession shows no signs of allowing diversity of thought onto its stages.

Many actors and directors give the impression of refusing to believe that anyone could disagree with their views

Personally, I’m not crying out for right-wing theatre the way that I once was; I have no particular desire to see a two-hour encomium to Nigel Farage or an epic series of plays preaching the gospel according to Andrew Tate. Yet I would dearly welcome the advent of conservative voices into theatre, rather than their existence being suppressed and shouted down.

Many artistic directors and leading actors give the impression of refusing to believe that anyone could possibly disagree with their doctrinaire and increasingly anachronistic political and social views; you will watch this play, you will accept this set of beliefs and you will leave the theatre a better person for doing so.

✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍ ✍

Like most Critic readers, I am not prepared to be talked down to by the theatrical incarnation of the nanny state. If the profession wants to argue with itself about whether Richard III must always be played by a disabled actor, or whether a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream must carry a strong pro-Palestinian message in order to remain “relevant”, let it. But this is not something that makes me believe that the eventual productions will be better or more interesting for the discussions and debates that have taken place along the way.

Great theatre, as its practitioners and critics alike have always known, does not come from the comforting soma of people agreeing with one another. It should challenge, provoke and enrage on occasion, just as it should make audiences fall onto the ground with laughter at other times. It should thrill, confound, devastate and elevate. The very best examples of the form can do all those things at once.

I cannot promise that every review I write will be laudatory or hilariously damning. I’m not going to watch plays I suspect will be bad in order to sneer at them; life’s too short for that. But what I do promise is that I will be fair-minded, tell the truth as I see it and refuse to be bamboozled by empty spectacle and emptier virtue-signalling.

Being invited to review theatre — an art form I have loved since I was a small child going to the Bristol Old Vic — is a privilege, and I will not let you down. As it is said in that estimable Pixar film Ratatouille, “a critic truly risks something, and that is in the discovery and defence of the new”. That is my challenge. See you in the stalls.