This article is taken from the April 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

The sample is too small to make it anything other than a curious fact that many painters who were also poets have often been marked by a non-standard psychology. Under today’s clinical terms, Michelangelo probably suffered from depression and anxiety; William Blake was prone to melancholy, the “shakes” and hallucinations; Edvard Munch’s fragile mental health was exacerbated by alcohol and veered close at times to schizophrenia; whilst David Jones most likely suffered from PTSD after his experiences in the First World War.

There is no hard and fast link. Other painter-poets such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paul Klee and Picasso, for example, all had their quirks but nevertheless passed as fully functioning personalities.

An intriguing painter-poet who falls into the first category is Zhu Da (1626–1705), also known as Bada Shanren. His cousin, the painter Shitao, described Zhu Da in verse: “Sometimes, to strangers, he plays the mad man;/His heart is strange, his ways are strange,/wild, heedless his outlook;/With brush aslant, ink dancing, he finds his true sāmadhi [state of beatitude]”. The lines are open to interpretation: was his madness real or assumed?

This ambiguity may have something to do with Zhu Da’s personal history. He was born a prince of the Ming dynasty and as such found himself in real danger when, in 1644, the Ming were overthrown by a Machu army and Zhu Youjian, the last Ming emperor, hanged himself in a pavilion overlooking the Forbidden City.

Zhu Da fled for safety to a Buddhist monastery in the mountains, took the name Xue Ge (“snowflake”, one of the 40 pseudonyms he used during his life), shaved his head and became a monk — reasoning that Qing vengeance would not seek him out in this guise.

Nevertheless, this abrupt change of life and the death of his father at around the same time seems to have triggered some form of mental collapse. As well as developing a speech defect, his behaviour became increasingly erratic. Indeed, he may have adopted the name by which he is best known, Bada Shanren, “Mountain Man of the Eight Greats”, because its Chinese characters resemble the words for “laugh” and “cry”, two interchangeable states that marked his character.

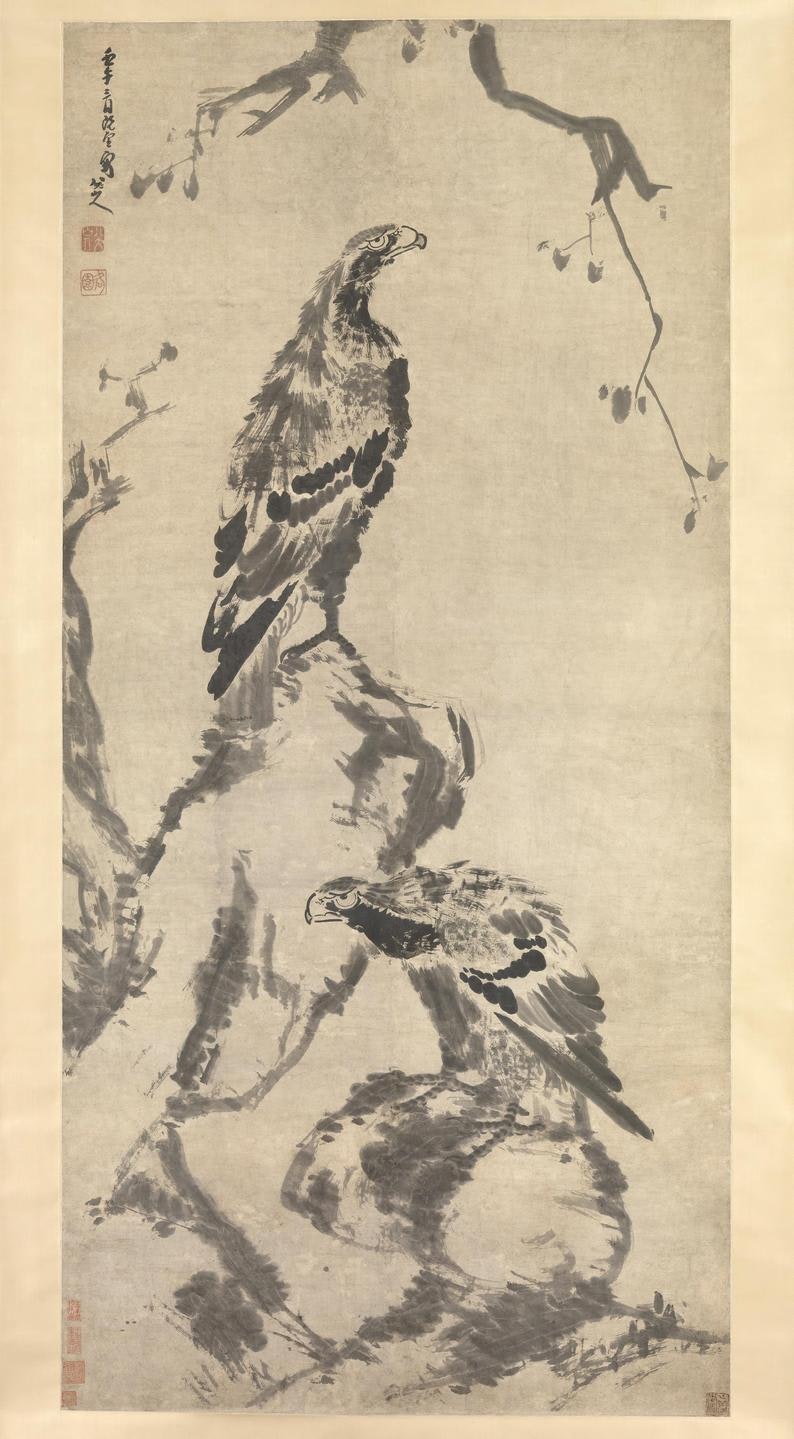

By the age of eight Zhu Da had demonstrated a wide-ranging artistic precocity and became an accomplished calligrapher and seal carver — skills held in high esteem — as well as a painter and poet. His ink drawings, usually of birds, fish, foliage and landscape, are marked by their vigour, distortion, force and often near abstraction.

He made little attempt to portray the reality of nature but rather its essence. Fish float in empty space, rocks become mere lumps and nodules, leaves overflow the edge of the paper sheet, a bird stands on one leg with a manic look in its eye whilst another pecks gleefully at a mass of grey splodges — there is wit and life in them all.

In his poetry Zhu Da would hint at his circumstances and the rule of the upstart Qing, but his paintings are concerned with the universal order of things.

His behaviour was just as distinctive as his art. During one episode he tore up his monk’s gown and ran through the local market, dancing and waving his tattered sleeves as local boys followed and laughed at him; he wrote ya, the character for “dumb”, on a fan and when he didn’t want to take part in a conversation he simply raised the fan.

Later he pinned a sheet of paper bearing ya to his door and refused to speak another word. The offer of drink, however, would make him laugh out loud which, several cups in, frequently turned to sobbing.

Drink freed his creativity and he would, according to a witness, “bare his arm and grasp the brush, at the same time emitting loud cries like a madman. The ink flowed abundantly without interruption. He would finish a score of sheets of paper or more in a trice. But when he is sober, you can’t get even a piece of paper or a mere character from him”. Sometimes he would use a broom or even his hair when making pictures.

He remained unbiddable and refused, as far as he could, to paint to order. He preferred to give his art to the poor rather than work for the privileged and powerful.

At some point in the 1680s, he felt secure enough to return to his hometown, Nanchang, and live as a professional scholar-painter. There he married — for the second time — but the union failed. His abbreviated style and his life as an eccentric were to prove highly influential to a succession of younger artists.

Whether he truly suffered a mental ailment was never properly established. As the contemporary scholar Shao Changheng wrote: “By acting suddenly mad, or suddenly mute, he can conceal himself and be the cynic he is. Some say he is a madman, others say a master. These people are so shallow for thinking they know Shanren. Alas!”