“Liberation Day”: That is what US President Donald Trump has called Wednesday, April 2, the day he announced huge swaths of taxes on imports worldwide. Despite the label, it was far from a day of liberation. By making imports to the US more expensive, the government is actively increasing the cost of living for American consumers.

The Trump administration has fallen for one of the most common misconceptions about trade—that it only benefits a country when it is the exporter. This could not be further from the truth. One of the greatest benefits of free trade lies with the importing country, where consumers gain access to a huge range of goods, crucially, at lower prices.

Whether it’s clothes, food, medical supplies, or mobile phones, access to the global market reduces the cost of living and increases consumer choice, often alleviating poverty in the process.

It comes down to a very simple principle. No one person could produce everything he or she consumes. No family or household could do so either. No city, town, or province could produce absolutely everything they consume. Equally, no country can produce everything it consumes, nor should it. Attempts to achieve autarky are acts of economic self-harm. Freedom to exchange across borders is win-win: it allows consumers to access a plethora of goods and services, improving welfare overall.

The theory behind these economic benefits is most clearly illustrated by the economists Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and John Stuart Mill.

Adam Smith, in his 1776 Wealth of Nations, emphasized the benefits of specialization through the division of labor. Trade improves welfare by allowing people to concentrate on whatever they can do best, meaning they become even better at it, and productivity increases. He used the example of the pin factory, where each worker is able to specialize in one particular stage of the manufacturing of pins.

David Ricardo took Adam Smith’s ideas even further. He showed that it is not even necessary for one particular country to have an absolute advantage to gain from free trade. Each party simply needs to focus on what they do best in comparison to the alternatives available. They have a comparative advantage.

John Stuart Mill developed these ideas, and argued that an increased openness to trade boosts productivity overall. For example, by allowing better equipment to be imported, allowing knowledge to be shared, and allowing for new competitive pressures.

Trade barriers, in the form of tariffs, quotas, and restrictions, impose artificial costs on goods and services moving across borders. In his first term, Trump’s tariffs on Chinese imports cost Americans over $800 per household on average. Tariffs create a lose-lose situation, in which consumers suffer by being forced to pay higher prices.

Tariffs also reduce output. On the whole, aggregated data show that tariffs have significant adverse effects on GDP.

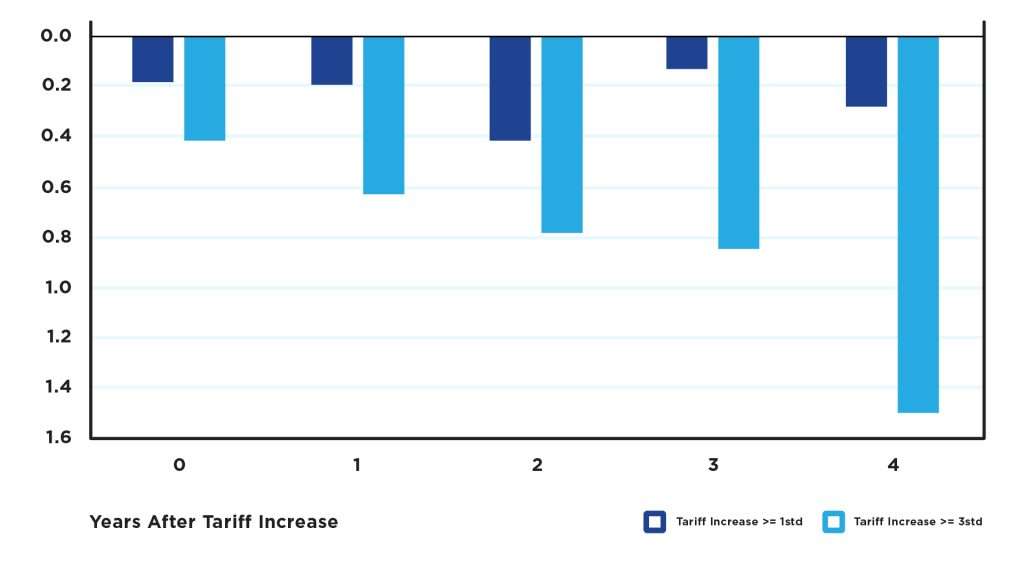

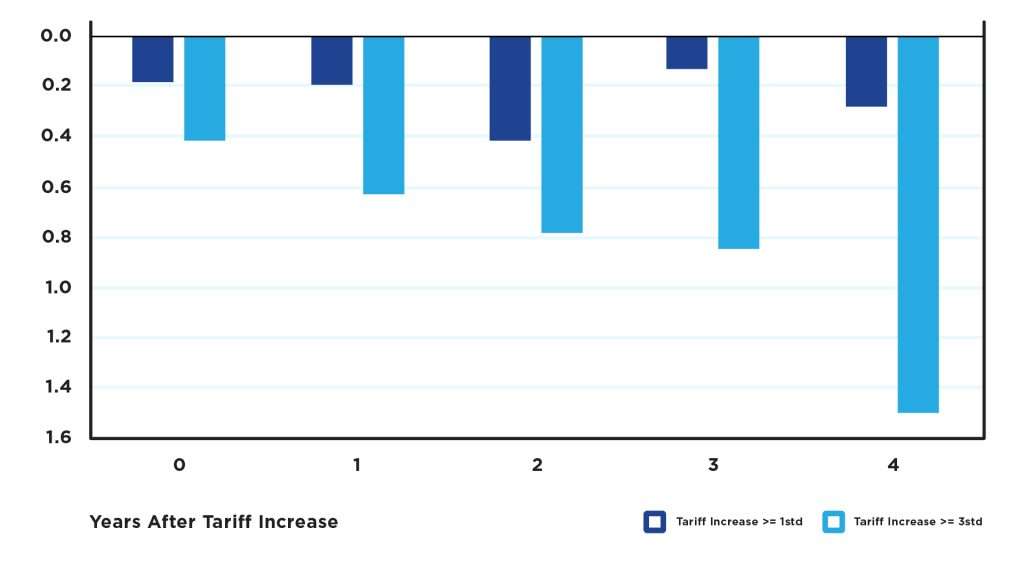

According to a 2020 study that looked at five decades of data from 151 countries, tariffs have a detrimental impact on economic growth:

The findings suggest that tariffs have a detrimental effect on output, with the negative effect larger for higher tariff increases and persisting over time, at least over the next four years [2021–2025] or so. The residualized growth tends to be in negative territory in all four years following an increase in protectionism. For example, after the second year, the residualized output growth is −0.4/−0.8 for one/three standard deviation(s) increases in tariffs, respectively. After four years, tariff increases are associated with an annual negative output growth of 1.5 percent when tariff increase is above three standard deviations.

All evidence points to the fact that trade barriers are bad for the economy, and bad for consumers. The long-term consequences of the US tariffs implemented this week are yet to be seen, but one thing is certain: Governments that introduce tariffs in retaliation will only hurt themselves.