Let’s start with the basics. The UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS) is designed to encourage a reduction in C02 produced by both large industry and fossil fuel powered generators. Everything from chemical producers, gas powered electricity and grey hydrogen are included.

It is, in simplest form, a Pigouvian Tax, a way of making the producer of a negative externality, in this case the producer of C02, pay for their negative externality.

The idea of the carbon market is that you create a market mechanism to find the clearing price where people will pay for their bad deed. This should be a more efficient solution then a centrally mandated tax level, due to increased price discovery. What we will now look at though, is the form and structure of this marketplace and whether it is actually efficient.

What is a Carbon Allowance?

The UK ETS is a cap-and-trade system which means that the Government caps the total amount of C02 allowed, then allows participants to trade within it. The UK ETS has been in place since 2021, but predates this, as previously it was part of the EU ETS, which was created in 2005.

The key building block is the Carbon Allowance. A Carbon Allowance is the right to produce C02, specifically 1 metric tonne of C02. Firms covered by the UK ETS, must show Allowances equal to the amount of C02 they have produced. By controlling the cap, the Government controls the supply.

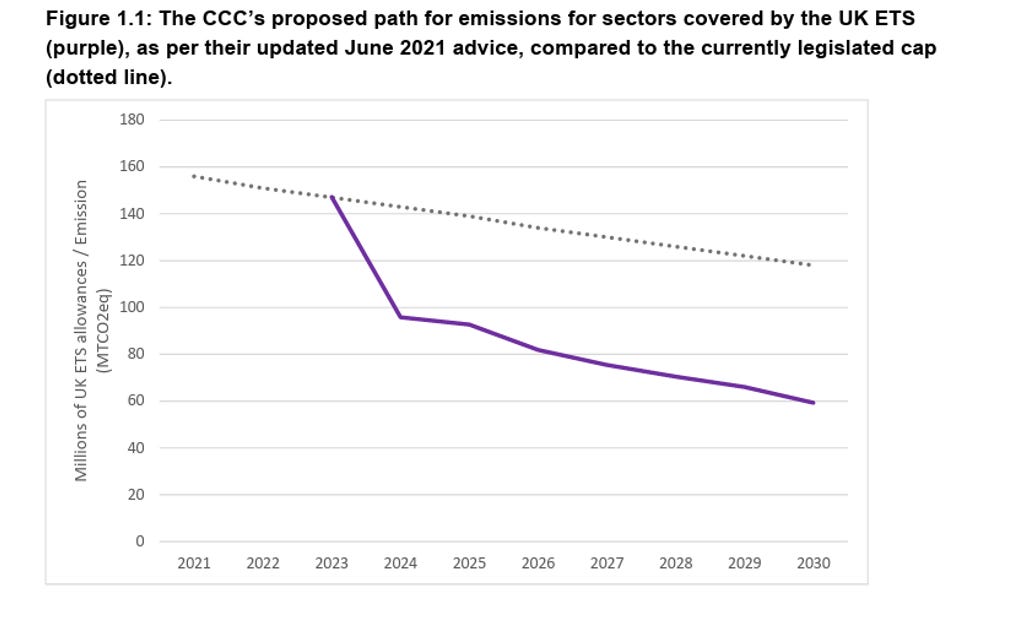

In 2023, the Climate Change Committee set the level of C02 at 936 million tonnes of C02 for the period 2021-2030, a reduction of 30% on the previous target and to align it with net zero goals. This means that only 936 million Allowances can be created by 2030. But how do you create an Allowance?

Well industry has a need to buy them, Government is the seller. This is where the trade component kicks in. The allowances are firstly sold in a primary auction (just like a government bond), then can be actively traded in the secondary market like a bond, in physical or derivative form.

Remember here, once the Allowance is used up it’s gone forever (think of it like using up your tank of petrol). Specifically, firms have until the April of the year after the reporting period to show proof of Allowances equal to their emissions. Once that’s done, those allowances are gone forever. The Government tightens the noose by reducing the supply each year, forcing over time the level of emissions to drop. This is shown below in a stylised way, but we’ll go into more detail shortly.

What do the auctions look like?

For those that of you with a penchant for legislation, it’s all set out in the Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Scheme Auctioning Regulations 2021, but for everyone else here are the highlights, with an effort to reduce the jargon. Every 2 weeks there is an auction, at which participants can buy Allowances. The auctions are an almost equal split of the yearly pot. Participants include those eligible for the ETS, but also bank intermediaries and Investment firms with MiFID Authorisation. That means industrials, airlines, banks, brokers and hedge funds are all eligible (this eligibility carries over into the secondary market too and will become important later).

The only other things to note now are that there is an explicit floor and implicit cap on the auction price. The floor is the Auction Reserve Price (ARP) and is set at £22 per metric tonne. The top side is a bit trickier.

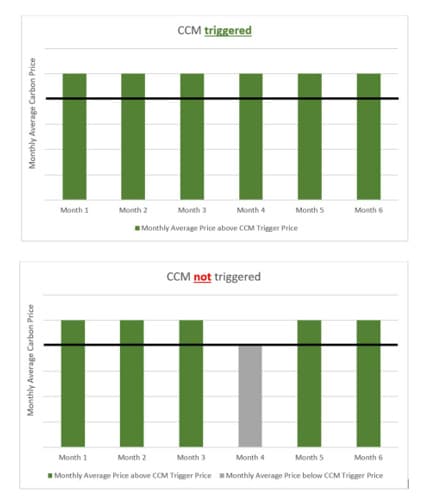

The Cost Containment Mechanism (CCM) kicks in if the secondary market price (in UK Allowance futures ordinarily) is more than 3x the rolling average for the last 2 years for 6 months consecutively. It’s fairly tricky to actually hit the mechanism because of its construction. Below from the government stylises the issue:

If triggered, there is no set response, the government can choose to increase the auction supply, but is under no obligation to do so. It’s more psychological and arguably acts as a ceiling to speculative accounts looking to push the price. In this respect, it’s akin to Mario Draghi’s infamous “ECB will do whatever it takes”.

If triggered, there is no set response, the government can choose to increase the auction supply, but is under no obligation to do so. It’s more psychological and arguably acts as a ceiling to speculative accounts looking to push the price. In this respect, it’s akin to Mario Draghi’s infamous “ECB will do whatever it takes”.

The eagle eyed may have noticed something

Well firstly, all the money in the auction process, goes to the Government, net of some fees to the auction manager for managing the process. Those proceeds are worth £16.93bn so far. Funnily enough, no one in Government has thought to mention that little dividend and presumably it has been lost down the back of the proverbial sofa.

The second thing is there is no natural expiry. Once you own an allowance, it will not degrade and only becomes worthless in a world where industrial emissions are 0. This is a crucial point because it means you can buy now and sell on later. Why would you do that? Well let me show you why, which is the same reason Hedge Funds have been buying current supply.

Beefing up the stylised scenario

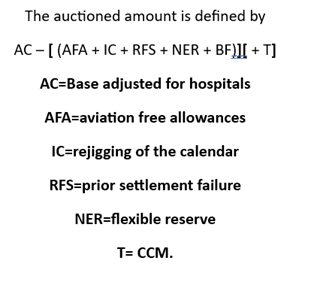

Buried in the legislation is this:

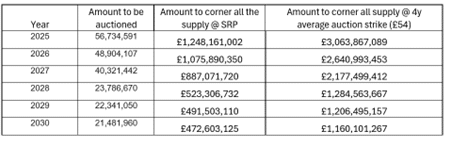

All the constituent numbers can be found in there also, although the AFA number required extrapolating what is a roughly constant depreciation rate. What does that mean for the next few years?

All the constituent numbers can be found in there also, although the AFA number required extrapolating what is a roughly constant depreciation rate. What does that mean for the next few years?

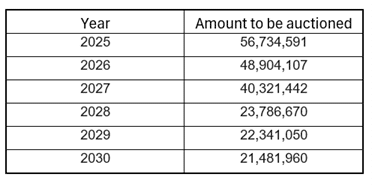

So by 2028 there will only be 23 million Allowances auctioned and 21 million by 2030. Now let’s work out how much it would cost to buy the entire auctioned supply:

As a very crude range, between £470m and £1.16bn. These might sound like big numbers, but these are pennies in financial market terms. To give a comparison. At JUST ONE UK Bond auction on the 3rd April 2025, the DMO will borrow £3.2bn in a 20y auction (There are over 70 in the financial year). This market looks absolutely prime to be squeezed and is a major threat to the economic prosperity and stability of the UK’s industrial base.

Very valid caveat

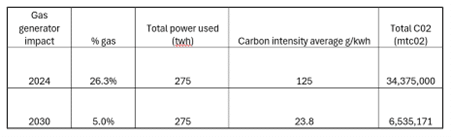

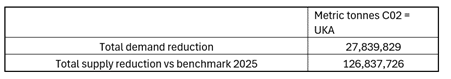

Clean Power 2030 dictates that by 2030 less than 5% of electrical energy can be sourced from Gas. This will forcibly remove demand for allowances. Let’s plug that back in and see what we get.

In 2024 according to NESO, the UK used 275 Twh of electricity, of which 26.3% was from gas. Our energy had a carbon intensity of 125g C02/kwh. Taking that down to 5% you get:

This means in total you get the below:

The reduction in supply is 4.5x the demand reduction and means by 2030 there will be a 98.998 million metric tonne of C02 decrease in UK emissions, by construction.

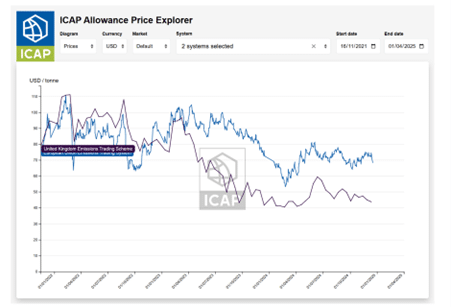

The second thing is in the name. The UK ETS. Post Brexit, UK allowances are not fungible with EU Allowances. In 2024, the cap for the EU ETS was 1.386bn allowances. Good luck squeezing that to the same extent.

When you combine it with the constructed reduction in supply, this is why ultimately the UK ETS is so fragile.

Why does this matter?

Time to pop a trader hat on again. Start by looking at the price you get in at. Given the floor (SRP) is £22, (albeit I’m sure in practice there is some arbitrage around it), if you buy at £54, that’s 40.7% of your starting value. At £37.48, where the average auction strike has been since Jan 24, that’s 58.6%.

If you were to buy a bond at 100 and your worst case is a recovery value of between 40p and 58.6p on every pound you spent, you’d be very happy if you were buying junk bonds. The key is this is a risky investment so your cost of margin and hurdle rate should be relatively high, but relative to other junk bonds a recovery rate here would be a steal.

This is obviously just your downside, but your upside is 3x your initial investment (if not more). Probability weight that to the upper side and you can see why hedge funds have been rushing to buy up the free float. US Junk bonds, or high yield, are around 7.5% with worse recovery rates, it looks like a no brainer, albeit one with possible downside.

This is a disaster in the making. What happens if suddenly the cost of your emissions increases 3-fold? If current levels are making the likes of INEOS uncomfortable, that’s really nothing compared to the future.

From an energy standpoint, as we get closer to CP 2030, Gas generated energy should by construct become very expensive, making all other forms look like a better trade off and so green alternatives better by construction, facilitating Clean Power 2030 endogenously.

Back to Pigou

The point of a Pigouvian Tax is to ensure that the negative externality producer pays for it. The issue is quantifying that externality. If the rate of supply reduction outstrips the capacity of industry to respond, the price will shoot higher and force industry to close. When you add in animal spirits that can amplify this effect by cornering the market, the implications are vast.

The Carbon Allowances market really captures the core of the debate around the pace of net zero. Is the pace too quick? Is it hurting industry? Is there a price you can put on the planet? Are there unintended consequences of the drive to net zero? All these questions are wrapped up neatly in this one problem.

So what’s the solution?

The FCA, in its oversight could help. Setting strong concentration limits for non-industrial accounts. But this feels like papering over the cracks somewhat, plus the issue is more 100 hedge funds own 75% of the free float, then one owning 50%, so you’d have to limit sector concentration, which is harder to pull off.

Secondly you increase the supply of allowances. There are two ways, firstly you soften the supply drop, secondly you re-join the EU single market.

Say you bin the stick and go bigger with the carrot. Just one problem there, how do you afford it? The UK ETS has been a nice source of revenue for the Government and with such tight fiscal headroom, they arguably cannot afford to lose this little money spinner. So, if you bin the stick, you bin your net zero pledges.

For now, it looks like the latter path is the one the Government will choose. Funnily enough, the Telegraph has been running pieces on the UK re-joining the EU ETS:

Leaving aside all the obvious pros and cons of EU membership, I’ll leave that debate to others, EU Allowances trade with an almost 50% premium:

This would add £25 to your current annual energy bill, with the industrial charges seen elsewhere in your household and economy wide finances.

There is no silver bullet, especially if we stick to the current timelines for decarbonisation. In summing up then, the raison d’etre of everything I write on is to provide people with the information, in an agnostic manner. It is then up to us all to work out which bills we do and don’t want to pay. Is this one we will pay? I’ll leave that to you to decide, hopefully I’ve helped clear it up a bit.

Nicholas Leighton-Hall is an energy consultant and the author of the Marginal Cost of Everything blog.