This article is taken from the April 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

On Boxing Day last year, we went on a family expedition to visit Bataville, the 1930s Czech village which exists surreally off the main road to Southend-on-Sea, as if it was the very first piece of land that Thomas Bata found when he was flying from Prague to London looking for somewhere to locate a new shoe factory.

After an excursion to see, but not to eat in, a modernist café, the only building ever designed by Ove Arup, on the seafront on Canvey Island (I don’t recommend it), we decided to drive back by way of Brentwood Cathedral, which in 2022 was listed Grade 2*, an unusual inclusion among recent listed buildings in that it is determinedly classical, designed by Quinlan Terry, a hero to the latter-day neo-classicists including the late David Watkin.

It was described by Nigel Huddleston, the heritage minster at the time as the “first classical cathedral built in the country since St Paul’s, its stunning design deserves this recognition and the listing will help to preserve the cathedral for generations to come”.

Over the years, I have seen quite a few buildings designed by Terry, not least because from 1995 to 2003, my nephew, George Saumarez Smith, worked for him, having trained as a classical architect in Edinburgh.

They include a commercial development next to the River Thames which caused a stir at the time it opened in 1987 because it looked as if it belonged in Richmond, Virginia as much as Richmond, England, designed in a style of loose-fit, pattern-book Palladianism much favoured by American architects after the Revolution because they were inclined to take their architectural idiom from books, unable to study their originals in the Veneto and Rome.

Indeed, Terry has, not surprisingly, designed buildings for Colonial Williamsburg, the Rockefellers’ wonderful, make-believe Georgian town on the south side of Chesapeake Bay.

At Downing College, Cambridge, Terry designed the Maitland Robinson Library which greets one as one arrives into the college. It fits remarkably well alongside the stiff, somewhat doctrinaire neoclassicism of its original scholarly architect, William Wilkins, a declaration of faith in the virtues of classicism, but perhaps without the visual pleasures and economy of Caruso St. John’s conversion of an old bicycle shed into the Heong Gallery.

On the north side of Regent’s Park, Terry was commissioned by the Crown Estate in the late 1980s to design a series of neo-Palladian villas which are so correct in their detailing as to be a bit lifeless, as if they were designed, as indeed they were, to show how it was still possible to produce classical buildings in the late twentieth century without deviating in any way from Palladio and Vignola, with none of the intellectually sophisticated playfulness demonstrated by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown in their nearly contemporary jazz version of classicism in the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery.

Seeing these works had not prepared me for the quality and serene interest of Brentwood Cathedral, which is a totally convincing reinvigoration-cum-reinterpretation of the classical tradition, with its very orderly and un-self-important courtyard to its north where one enters from the north-east corner through a long, horizontal façade of Kentish ragstone interspersed by Portland Doric pilasters and with a central semi-circular portico for special occasions, based on the south portico of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

One feels as if one might be somewhere on the eastern seaboard of the United States where classicism has retained an everyday utility much longer than on this side of the Atlantic.

Even more persuasive and visually satisfying is its Quattrocento interior, centrally planned, with surrounding columns obviously indebted to the façade of Brunelleschi’s Ospedale degli Innocenti, but done with confidence, not just an imitation. Its Quattrocento character is reinforced by the Stations of the Cross by Raphael Maklouf in terracotta roundels in the spandrels of the arcades.

There is also something of the pragmatic classicism of Christopher Wren’s city churches, which Bishop Mahon who commissioned Terry rightly and understandably admires, not least because, as in St. Stephen’s Walbrook, the altar is in the centre of the building, a simple marble table supported on Tuscan columns, designed by Terry and made of Nabresina stone from Pisa.

Beyond this calm, numinous space and behind the marble Bishop’s throne is the old Victorian church, designed by Gilbert Blount, a Catholic architect who had worked under Brunel as a civil engineer before training as an architect in the office of Sydney Smirke.

The nave of the Victorian church contains semi-circular choir stalls and an organ which came from a redundant church in Colchester and has been installed in a case also designed by Terry.

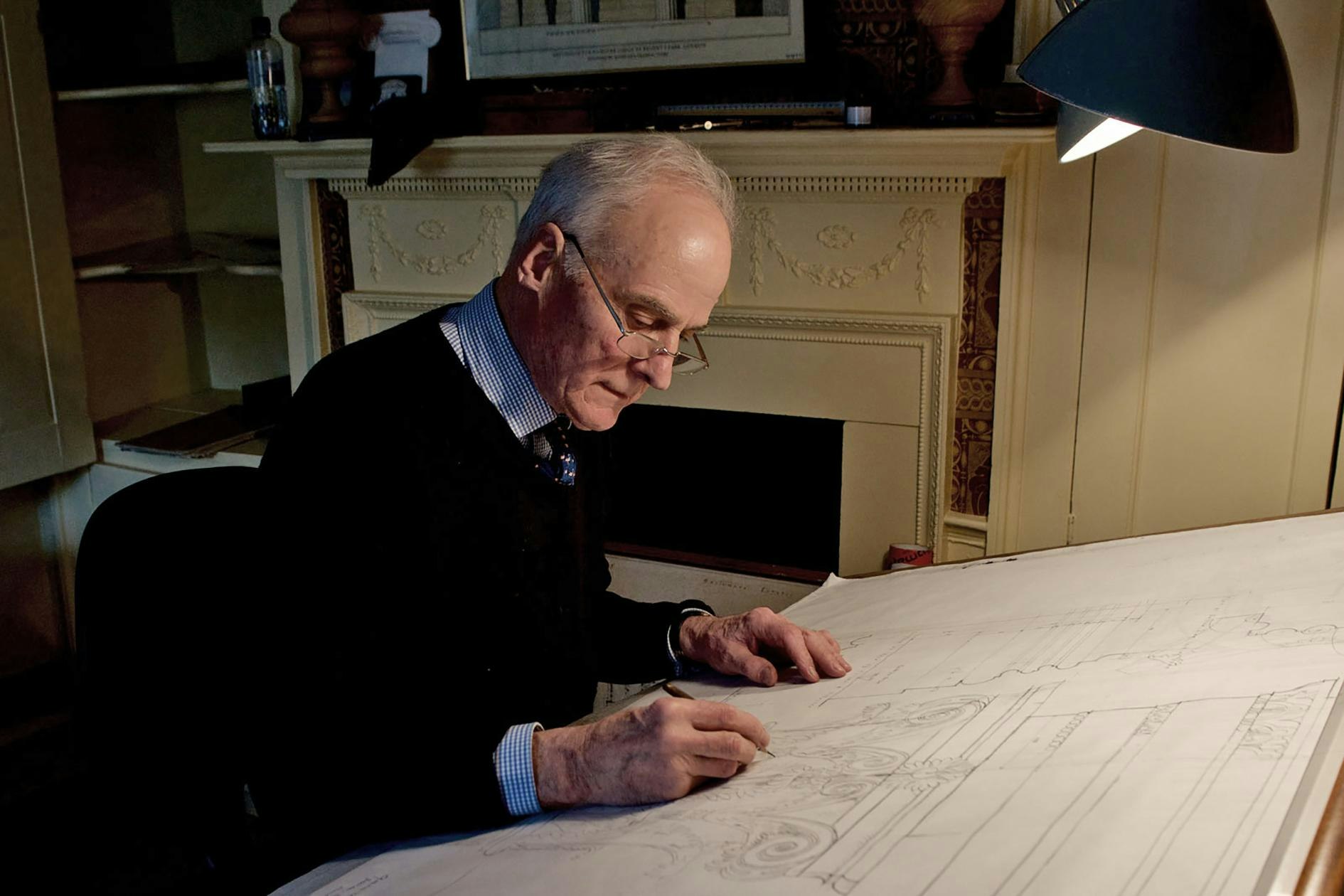

Terry himself has not necessarily been the most effective advocate of classicism because, after studying under James Gowan and Peter Smithson at the Architectural Association, he joined Raymond Erith’s practice in Dedham in 1962, which enabled him to retreat from all aspects of modern life.

He regards classicism as having been handed down to Moses on tablets of stone. But what Brentwood Cathedral effectively demonstrates is how well classical architecture can still work in an appropriate civic and ceremonial setting, providing a calm, orderly environment for the celebration of Mass and private prayer.

When we visited there was a man who looked as if he was seeking consolation from some private grief. The cathedral was an appropriate place in which to find it.