This article is taken from the April 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

No-one had a keener eye for Émile Zola than Cézanne. And no wonder. They were boyhood friends. Having grown up together in Aix-en-Provence, they kept up a lively — at times, even faintly homoerotic — correspondence even long after they had both become famous.

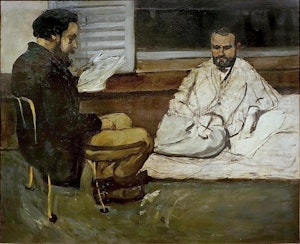

Over the years, Cézanne drew or painted the novelist several times; but perhaps his most revealing portrait is now in the São Paulo Museum of Art. Painted in 1869/70 — just as Zola was embarking on the vast Rougon-Macquart series of novels — it is really a double portrait. On the left sits Paul Alexis, a young journalist, who had recently arrived in Paris from Provence, and who would go on to become Zola’s first biographer. He is reading aloud from a manuscript, with his legs crossed nervously under his chair.

Meanwhile, Zola sits — or rather, reclines — on the right. He has an almost Buddha-like calm. His brow is furrowed slightly; his lips pursed in thought. But his gaze remains inscrutable. What he thinks, or how he feels, is a mystery.

It is eerily fitting. Despite Zola’s dream of writing for “everybody”, few French writers have been so elusive, or so polarising. Within a few decades of Cézanne’s portrait, his novels would be hailed as the acme of naturalism and vilified for their “obscenity”, while his defence of Alfred Dreyfus — the Jewish officer falsely convicted of spying for Germany — would both force him into exile and earn him a hero’s laurels.

Even Zola himself was unsure of who he wanted to be. He went to great lengths to cultivate a public persona that was often quite different from his private life. Despite the overtly political character of many of his novels — especially L’Assommoir (1877) and Germinal (1885) — he eschewed any party, preferring to cast himself merely as “a respectable bourgeois”. He studiously crafted an image as a serious, even austere figure — a writer to his fingertips. Yet when Henry James met him in London in 1893, he found Zola bristling with anger at being “just” a novelist. So desperate was his desire for recognition that he made no fewer than 19 unsuccessful attempts to be elected to the Académie Française.

So who was the real Zola? What did he really think — and why? What made him so popular and so divisive? And why should we read him today?

The key was not just to observe, but to experiment using his characters

Robert Lethbridge and Rachel Bowlby have set out to find the answers. Their books are ostensibly very different: Lethbridge’s is a sober, scholarly, self- consciously literary biography, while Bowlby’s chatty little volume is more of a personal response to Zola’s works, or, as she puts it, a kind of “extended advertisement” for his writing. Yet, in their different ways, they each have the same goal, and adopt a broadly similar approach. Put simply, they try to understand Zola’s worldview through his works, and his works through their context.

This is not only sensible but illuminating. As both Lethbridge and Bowlby stress, Zola’s career as a writer was determined by his experience of the realities of nineteenth-century French life. Unlike Proust, for example, he wrote not simply from aptitude, but out of necessity. His father, a failed engineer of Venetian origin, died while Zola was barely seven years old, leaving him and his mother almost destitute.

His earliest years were spent dotting between threadbare lodgings in Paris, living largely off the kindness of the family lawyer; he knew that as soon as he was able, he had to earn a living. His mother wanted him to become an engineer, like his father. But after twice failing his baccalauréat, he had to look elsewhere. Only by sheer luck did he eventually land a post at the publishing firm of Hachette — first as a distribution clerk, then as a member of the publicity department.

As Lethbridge notes, this “provided him with an ‘education’ far more instructive than his school curriculum”. It encouraged him to try his hand not just at fiction, but also at journalism, where he was free to explore different views; it taught him that writing was a job of work like any other; and it gave him an almost Stakhanovite self-discipline.

Most importantly, as Lethbridge argues, it also gave him an understanding of how to sell books — by “making … contact with reviewers, drafting enticing blurbs and exploiting opportunities for controversy”. Today, we would probably call this huckstering — but it was a lesson that served him well.

At a more fundamental level, Zola’s works were themselves inseparable from his age. From the outset, Zola saw the Rougon-Macquart as a form of history. Not just any history, though. He had no desire to ape Balzac’s La Comédie humaine. He had little interest in using his novels as a “mirror” — and none whatsoever in making moral judgements. Rather, his history was to be scientific.

As he explained in the spring of 1879, his method was analogous to that described by the physiologist Claude Bernard. The key was not just to observe, but to experiment using his characters — to explore through the life of a single family, how individuals are affected by their environment, in this case, the society of the Second Empire.

Each novel was intended to address a different social class or type; and each character was heavily informed by Zola’s reading of Prosper Lucas’ classification of “inherited physical traits and psychological tendencies”. In order to research locations, Zola — never much of a traveller — also forced himself to criss-cross France: “the mining country around Valenciennes for Germinal … the battlefields of the Franco-Prussian War for La Débâcle [1892] … Le Havre [for] La Bête humaine [1890].”

By the time Zola began writing the Rougon-Macquart, the regime of Napoleon III was already on its last legs, and most of the novels were published long after it had passed into memory. But this is not to say that the series was ever a static project. Quite the opposite: Lethbridge shows how radically it changed over time as a result of the shifting temper of the Third Republic, and changes in Zola’s own views. Its scope expanded from a projected ten volumes to 20; new books were needed to tackle themes Zola was slow to recognise (e.g. La Débâcle); and a constant dialogue was maintained with writers such as Hippolyte Taine, and artists such as Manet — whose works Zola championed.

Nor was Zola’s naturalism all that it was cracked up to be. As Lethbridge emphasises, his failure to anticipate the collapse of the Second Empire meant that he often had to play fast and loose with chronology. His characters are sometimes handled more with an eye to structural balance than for realism. And his need for resolution sometimes “opens up perspectives constrained by neither politics nor credibility”.

Yet, in other respects, he displays a far more astute insight into emerging patterns of social behaviour than has often been assumed. Telling in this regard is his depiction of shops in novels like Le Ventre de Paris (1873) and Au Bonheur des Dames (1883). In a fascinating chapter, Bowlby demonstrates that Zola had a surprisingly prescient grasp not only of the “dramatic new force of the department store” but also of the consumer culture that such milieux encouraged.

All this adds up to a much richer, more nuanced picture of Zola the writer. Despite their differences, Lethbridge and Bowlby each reveal him to have been a fundamentally dynamic novelist — evolving in step with the tempo of the times, continually thinking and rethinking the past, the present, even the future.

But Zola the man is strangely absent. Other than a few occasional flashes — the legacy of his disgraced father, the two children he fathered with the family maid — we never get to see Zola “in the flesh”. To some extent, this is only understandable. By focusing exclusively on Zola’s writings, neither Lethbridge nor Bowlby has much scope to engage with the more mundane aspects of life. And in their different ways, each of these books is superb. But still, it is hard to escape the feeling that Zola’s gaze remains just as it appears in Cézanne’s portrait — inscrutable.